“Give me six hours to chop down a tree, and I will spend the first four sharpening the ax.”

– Abraham Lincoln

Low Back Pain: Facet Joints

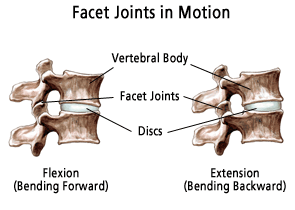

The facet joints, also known as zygapophyseal or “Z” joints, connect the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies to one another. They allow the spine to bend, twist and lean in different directions but they are restrictive in hyperflexion and hyperextension so that they may becone injured in extreme, forceful movements. Like other joints, such as the knee or elbow, the surfaces of the facet joints are covered by a layer of smooth cartilage, surrounded by a strong, fibrous capsule of ligaments, and lubricated by synovial joint fluid. And like other joints, the facet joints can also become arthritic and painful.

Facet joints can become painful as a result of repetitive stress and trauma, resulting in arthritis. The facet joints are the cause of pain in up to half or more of patients with chronic LBP. The prevalence of lumbar facet joint pain is age-related and more common in older populations especially when there is no history of trauma.

See Also:

Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

LBP – Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

LBP – Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

LBP – Surgery:

.

Low Back Pain: Facet Joints (FJ)

Facet pain may occur after an acute injury (eg, forceful extension and rotation of the spine that might occur in a motor vehicle accident), or it may be chronic in nature. Like arthritis, greater age increases likelihood of facetogenic pain.

Signs and Symptoms of Facet Pain

There are no signs or symptoms that are reliably specific for facet pain. Features suggestive of low back pain generated by facet joints (facetogenic pain) include a deep and achy quality that is usually localized to a unilateral or bilateral paravertebral area but not in the midline. Historical features that increase the likelihood of facetogenic pain being present are age greater that 65 and improvement in pain by lying flat on your back (supine). Facetogenic pain is often worsened by twisting the back, by stretching, and by lateral bending, especially in the presence of a torsional load. Some patients describe their pain as worse in the morning, associated with stiffness (typical of arthritis), aggravated by rest and hyperextension, and relieved by repeated motion.

Other features include pain that is not worse with forward flexion including sitting and not worse when rising from sitting to standing. Unlike other lumbar spine pathologies such as disc herniation, facet joint pain likely will not worsen with an increase in intra-abdominal and thoracic pressure. Therefore, worsening of pain with coughing, laughing, or a Valsalva maneuver is suggestive that the facet joint is not the primary pain generator.

Referral Patterns

The common referral areas for facetogenic pain are flank pain, buttock pain (often extending into the posterior thigh, but rarely below the knee), pain overlying the iliac crests, and pain radiating into the groin.

In severe case of FJ pathology, hypertrophy (enlargement) of the FJ especially if coupled with bone spurs or bulging discs, can lead to compression of an adjacent nerve root. This can trigger neurogenic pain from the nerve root radiating down the leg (sciatica). Nerve root involvement can produce a radiculopathy: paresthesias (tingling sensations), decreased sensation, loss of muscle strength, and diminished or absent deep tendon reflexes along with pain referred down the leg.

Physical Examination

As is the case with signs and symptoms, there is no finding on physical examination that reliably identifies facetogenic pain. Replication or aggravation of pain can be elicited by unilateral pressure over the FJ or transverse process. Pain improves with flexion and worsens extending the back backwards or extension plus side bending or rotation to the ipsilateral side.

Imaging studies

Most people with even mild to moderate amounts of arthritis of the lumbar spine will have evidence of facet joint degeneration on an x-ray, CT scan (CAT scan) or MRI.

A bone scan, which shows areas of active inflammation in the spine, is a test that can be used to determine whether or not facet arthropathy may be contributing to a patient’s back pain.

Diagnostic Procedures

Due to the lack of reliable findings by history, physical exam or on imagine studies that can accurately identify facetogenic pain, the most accurate means of establishing a facet joint as being painful is to anesthetize the joint. If anesthetizing the joint successfully relieves the targeted pain, it is believed to be reliable. That being said, however, even the anesthetizing procedures are not entirely reliable due to variables in placebo response and some degree of inability to accurate reproduce the diagnostic procedure. It is therefore common to not rely on one positive diagnostic injection, but require a second confirmation block. There still remains controversy regarding the interpretation of multiple injections.

There are two types of diagnostic blocks:

Intra-Articular Blocks

Intra-articular blocks involve the direct injection of anesthetic into the facet joint under fluoroscopic x-ray guidance. As a control, saline is sometimes injected to help rule out false positive anesthetic injections.

Medial Branch Blocks

The nerves that carry pain signals from the facet joints are the medial branches of the local spinal nerves. Injection of a local anesthetic that blocks these nerves, called a medial branch block (MBB) can block pain signals and positively confirm the specific nerve carrying the pain signals. A MBB is commonly used to identify the specific nerve coupled with a suspected facet joint thought to be the generator of LBP. However, adjacent structures including the multifidous paraspinal muscles are also innervated by the same medial branch and may also be pain generators.

Medial branch blocks have been shown to be safe. That being said, there is a lack of consensus regarding their interpretation. Some guidelines call for at least two succesful MBBs to confirm accuracy of

the diagnosis of facet-generated pain. The degree of pain relief neccesary for a positive response is also a point of contention. At least a 50% or greater reduction of pain is required by some protocols to confirm a positive response, others protocols call for a 75-80% and up to 100% or greater relief of pain for confirmation. In contrast, some argue that a prior MBB is not necessary to proceed to a radiofrequency ablation (see below).

Treatment of Facetogenic Pain

Treatment Based on Mechanisms of Facetogenic Pain

It is believed that the basis of facet-generated pain stems from degenerative and inflammatory processes suggesting the dominant mechanism of pain to be nociceptive. This is also consistent with the common descriptions of facetogenic pain to be dull and achy in character. For this reason, medical management of facetogenic pain should likely focus primarily on medications directed at nociceptive pain including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and when required, opioids.

Occasionally, synovial cysts (out-pockets of the facet joint synovium, the membrane lining the joint) may be painful. Most often, they cause foraminal or spinal stenosis. Typically, on T2-weighted MRIs, synovial cysts are seen as rounded areas of increased signal intensity with a peripheral rim of decreased signal intensity. These cysts are located adjacent to a facet joint. The injection of steroids into the associated facet joint is effective in resolving synovial cysts in 30-40% of patients, although repeated injections may be necessary.

Due to the inflammatory role in facetogenic pain, other therapeutic measures directed at osteoarthritis would also likely be helpful.

See: Osteoarthritis

There is some research that suggests a component of neuropathic pain in the pain of arthritis. If a patient appears to have symptoms suggestive of neuropathic pain including sharp, stabbing, burnng or electric-like pain, a trial of neuromodulators should be considered.

See: Neuropathic Pain

Physical Therapy

The benefit of physical therapy has been well established for facetogenic pain but must be individually assessed and directed.

Treatment Procedures

Facet Injections (Intra-Articular Steroid (IAS) Injections)

The facet joints can be selectively injected with a mixture of a local anesthetic and an anti-inflammatory steroid (like cortisone) in the same manner commonly employed for painful, arthritic shoulders and knees. Pain relief can sometimes be significant and last for weeks or up to 3-6 months but unfortunately, while definitive studies are still lacking to identify accurate response rates, it appears that less than 50% of these procedures provide significant, lasting relief.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)/Radiofrequency Neurotomy

When suspicion of facet joint-mediated pain is supported by two successful diagnostic medial branch blocks, consideration of facet joint denervation may be appropriate. Facet joint denervation is achieved by radiofrequency lesioning (ablation) of the identified nerve, also referred to as a “neurotomy.” This is accomplished by burning the nerve through the application of an electrical impulse. The burning of the nerve is hoped to achieve a signiicant reduction of pain for 6-12 months.

The median time for return of at least 50% of preoperative pain level was found to be 263 days in one recent study. In this study, 87% of patients obtained at least 60% relief of pain and 60% of patients obtained at least 90% relief of pain at 12 months. This procedure has a good safety profile and is commonly employed. However, there have been multiple studies investigating benefit of RFA and outcomes have been mixed, usually based on flaws in the study protocols.

Some clinicians have concerns about this treatment of “killing the messenger.” While there is an established benefit of prolonged pain reduction, the concern is regarding the potential for pathologic re-growth of the burned nerve 6-12 months out. Burning a healthy nerve appears to place that nerve at risk for growing back abnormally with the potential for creating yet another pain generator with the new nerve. While there are apparently no studies available that evaluate the condition of the regenerated nerves, there do not appear to be any reports of bad long-term outcomes in this regard.

Conclusions

In 2013, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) released an update of their guidelines for interventional techniques in patients with chronic spinal pain. The guidelines state that evidence for the therapeutic effectiveness of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks is fair to good but that there is only limited evidence for the efficacy of intra-articular lumbar injections. The ASIPP guidelines also state that there is good evidence for the therapeutic effectiveness of RF ablation in lumbar facet joint interventions.

References

LBP: Facet Pain – Overviews

LBP: Facet Pain – Mechani

sms of Pain

- The Discriminative Validity of “Nociceptive,” ” Peripheral Neuropathic,” and “Central Sensitization” as Mechanisms-based Classifications of Musculoskeletal Pain – 2011

- Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians – 2010

LBP: Facet Pain – Interventional Procedures

- An Update of Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines for Interventional Techniques in Chronic Spinal Pain. Part I Guidance and Recommendations – 2013

- An Update of Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines for Interventional Techniques in Chronic Spinal Pain. Part II Guidance and Recommendations – 2013

LBP: Facet Pain – Referral Patterns

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.