“Vitality shows in not only the ability to persist but the ability to start over.”

– Scott Fitzgerald

LBP: Spinal Stenosis (Central)

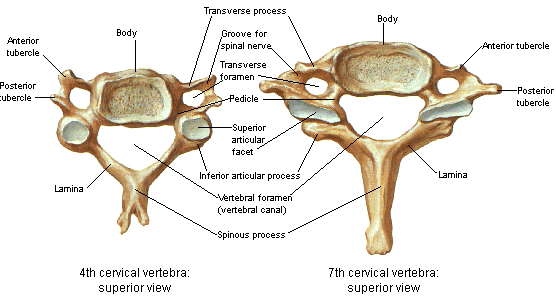

Central spinal stenosis (or central canal stenosis) is a condition that occurs when the spinal canal is narrowed, either congenitally or by enlarged ligaments, protruding discs, enlarged facet joints and/or bony overgrowth (spurs) and can occur anywhere along the length of the spine (cervical, thoracic, lumbar). The spinal canal is a space that extends the entire length of the spine which is filled with cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the spinal cord. Spinal stenosis can occur centrally or laterally and is a significant source of both neck and back pain as well as the pain that can radiate from the back down the legs (sciatica). Spinal stenosis is a common source of chronic post-operative pain in failed back surgery syndrome.

Stenosis, or narrowing, is most common in the lumbar spine, although most potentially dangerous in the cervical spine (neck). When severe, central spinal stenosis can cause compression of the spinal cord leading to back pain, pain in the legs, weakness, numbness and other symptoms including bladder dysfunction. Severe lateral spinal stenosis can lead to compression of nerve roots exiting the spinal cord causing severe pain radiating down the leg (“sciatica”).

See Also:

- Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

- LBP – Arachnoiditis

- LBP – Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

- LBP – Disc Pain

- LBP – Facet Pain

- LBP – Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

- LBP – Myofascial Pain

- LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

- LBP – Sciatica

- LBP – Spinal Stenosis

Treatment Procedures:

- Epidural Injections

- Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

- Heat & Cold Therapy

- Inversion Therapy

- Massage Therapy

- Physical Therapy

- Trigger Point Therapy

LBP – Surgery:

.

LBP: Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis affects about 1 per 1000 people older than 65 years and about 5 of every 1000 people older than 50 years. Lumbar spinal stenosis is the leading diagnosis leading to spine surgery in people >65 years old.

The two lower segments (L3-L4 & L4-L5) of the lumbar spine, because they provide the most motion, are most commonly affected by degenerative stenosis. These segments provide more rotation and are therefore more vulnerable to rotatory strains leading to degenerative changes that contribute to the narrowing.

Spinal stenosis can be either central or lateral. Central spinal stenosis (CSS) occurs in the midline. Symptoms from CSS are not generally not triggered by isolated disc bulges unless very severe or associated with herniation and extrusion of disc contents (Herniated Nucleus Pulposis or HNP) or other contributing conditions such as bone spurs or facet arthritis. In lateral spinal stenosis, narrowing of the lateral spinal canal can result in narrowing of the nerve windows (foramen) where nerves exit the spinal cord to extend down the legs.

Central Spinal Stenosis of the Lumbar Spine (LS)

Central Spinal Stenosis (LS): Causes

Congenital spinal stenosis (narrowing) is uncommon, affecting <10% of cases, and generally does not cause symptoms in the absence of other contributing factors. The risk for congenital spinal stenosis appears to be higher in low birth weight babies and greater maternal age. Other conditions that commonly contribute to spinal stenosis include thickening of the ligament that runs the length of the spine (ligamentum flavum hypertrophy), which can result from trauma or as a post-operative complication. Enlargement of the facet joints resulting from arthritis, bone spurs (osteophytes), vertebral body compression fractures, and herniated discs with extrusion of disc contents (herniated nucleus pulposus – HNP).

Systemic processes that may also contribute to in spinal stenosis include Paget disease, tumors, and ankylosing spondylitis. Infections of the vertebrae (osteomyelitis), discs (discitis), and local abscesses can also lead to stenosis and compression of the spinal cord.

Central Spinal Stenosis (LS): Signs & symptoms

Symaptoms usually start slowly and intermittently, usually in people older than 50 y/o. The characteristic pain pattern of lumbar central spinal stenosis is low back pain (LBP), especially buttocks (gluteal) pain, weakness and numbness or tingling in the legs associated with standing or walking, and complete or near-complete relief of pain with sitting or bending forward at the waist. Bending forward stretches the ligament running the length of the spinal canal, thinning it and widening the canal thus decompressing the nerve root(s) and relieving the pain. Because bending backwards in extension makes the stenosis worse, people with central stenosis in the lumbar area will experience pain when descending stairs and may be observed bending forward and leaning on their shopping cart while shopping to ease their pain. This symptom complex is quite the opposite of discogenic pain, but similar to facet pain.

The classic symptom of central spinal stenosis is leg pain, unilateral but most often bilateral, with walking or standing. While many if not most patients with spinal stenosis also report LBP, it is not common (<10%) for patients with central spinal stenosis to have primarily LBP and gluteal pain with little or no leg pain. Weakness of the lower extremities can also be found. The nerve root in the lumbar spine most commonly affected is L-5 which is associated with weakness extending the large toe on the affected side (s).

Claudication

Claudication, the term for pain in the legs associated with walking, can result from compromised blood flow to the leg muscles associated with peripheral vascular disease (vascular claudication) or from spinal cord compression associated with central spinal stenosis (neurogenic claudication). It is important to distinguish one from the other as neurogenic claudication may require emergency surgery to avoid permanent damage to the spinal cord. Patients with neurogenic claudication experience pain with walking almost as frequently as those with vascular claudication. Therefore this symptom cannot be used to discriminate between the two types of claudication. Both types also frequently experience the pain as cramping but there may be a greater likelihood that weakness of the lower extremities is more likely to be found with neurogenic claudication but this does not appear to be consistent between studies.

Neurogenic vs Vascular Claudication?

Neurogenic claudication is triggered by activities that apply weight or compression forces vertically along the spine (axial-loading), thought to compress the nerve roots and/or their blood vessels in the spinal cord and also narrow the spinal canal. This means that neurogenic claudication may be triggered just by standing, without walking, unlike vascular claudication. In fact, the absence of symptoms associated with prolonged standing is the strongest predictor that the claudication is not neurogenic but vascular. Unlike vascular claudication, neurogenic claudication is relieved by flexion and not by merely stopping walking. Also, vascular claudication pain frequently extends

below the knee whereas neurogenic claudication usually does not progress past the buttocks or thighs.

In vascular claudication, findings of compromised blood flow to the lower extremities may be evident including reduced pulses in the feet, loss of hair on the feet, pale appearance along with pain and/or tingling in the lower extremities.

With claudication associated with all 4 of these findings, the likelihood of it to be neurogenic is 98%:

1- Pain is triggered by standing

2- Pain is relieved with sitting

3- Pain is limited to above the knees

4- Positive “shopping cart” sign (see above)

With claudication associated with both of these findings, the likelihood of it to be vascular is 97%:

1- Pain is relieved by standing

2- Pain is located in the calves

Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES)

When central stenosis in the lumbar area becomes severe and compresses the spinal cord, neurologic dysfunction may occur with symptoms including urinary retention or, less frequently, incontinence (leakage), weakness of the lower extremities and numbness in the perineal area which extends between the anus and the genitals. Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES) may represent a neurosurgical emergency so these symptoms should be reported to your physician ASAP and evaluated in an emergency room.

Central Spinal Stenosis (LS): Physical Exam

In the absence of spinal cord compression, any symptoms relative to central stenosis will reflect the underlying factors contributing to the stenosis. With spinal cord compression however, increased reflexes may be evident, weakness and/or numbness of the lower extremities and findings of cauda equina syndrome may be present which suggests the potential for a surgical emergency. Because the L-5 nerve root is most commonly affected weakness extending the great toe may be evident.

Loss of lumbar lordosis, or extension of the lower back is the most consistent finding on exam. Walking in forward flexion may be observed. Some form of neurologic deficit is found in about half of affected patients.

Central Spinal Stenosis (LS): Diagnosis

Imaging Studies

Central stenosis cannot be identified with routine x-rays but will be visualized on CT or MRI scan but the MRI is the preferred choice. Nerve conduction studies may help distinguish from other neurologic conditions. The severity of central canal stenosis findings on MRI do not predict severity of neurogenic claudication symptoms, nor does severity of arterial flow on ultrasound evaluation of the lower extremities necessarily predict severity of vascular claudication.

Central Spinal Stenosis (LS): Treatment

Successful management of chronic LBP often requires an “integrative” approach, that is a treatment regimen that integrates a multi-disciplinary collection of treatment options that include education, exercise, trigger point therapy, massage, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, diet and nutritional supplements, medications and mind-body disciplines such as yoga and tai chi. These topics are covered elsewhere on this website.

The best predictor of function in those with lumbar spinal stenosis is body weight, with significantly greater loss of function in those with BMI >30. Weight loss is therefore an important consideration in this population.

Medications

The pain associated with central stenosis is commonly neuropathic (nerve) pain and is treated with neuromodulators including gabapentin (Neurontin), pregabalin (Lyrica) and tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline (Elavil) or doxepin.

See Neuropathic Pain

Epidural Steroid Injecions

See: Epidural Injecions

Surgery

The goal of surgical treatment is to achieve nerve decompression adequate to provide relief from symptoms, while preserving, as much as possible, the anatomy, stability, and biomechanics of the lumbar spine. Surgical approaches may be “open,” (making an incision and directly visualizing the procedure) or endoscopic, with the goal to decompress the affected vertebrae with a laminectomy and fusion.

With standard decompressive laminectomy surgery, a 2015 study indicated that there is greater statistical improvement in symptoms for up to 4-8 years after surgery compared with non-surgical management. However, there may be less advantages for surgery after the first four years. About one patient in five required additional surgery within the eight years. Patients in this study ha

d a minimum of three months of symptoms and had failed conservative therapy including physical therapy, chiropractic treatment and medication management. The surgery was considered safe with no serious complications such as paralysis or death.

The MILD Procedure (Minimally Invasive Laminotomy and Decompression)

A less invasive approach is MILD, a minimally invasive alternative to open or endoscopic surgery for lumbar decompression in the treatment of spinal stenosis. MILD is an outpatient procedure performed using IV sedation or monitored anesthesia care and consists of partial removal of interlaminar bone (laminotomy) and partial excision/removal (debulking) of the ligamentum flavum and fatty tissue from the posterior aspect of the lumbar spinal canal.

Some physicians have suggested that the MILD procedure should be offered only to those with symptomatic central stenosis when MRI clearly shows it is only or mostly caused by ligamentum flavum hypertrophy. Patients should be advised that MILD may not help their back pain or their radicular symptoms.

Other minimally invasive procedures are available and surgical options are best deferred to qualified orthopedists and neurosurgeions.

Lateral Canal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) of the Lumbar Spine (LS)

Lateral Spinal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) – LS: Causes

Causes of lateral canal stenosis include disc herniation, especially when associated with extrusion of disc contents (herniated nucleus pulposus – HNP). Facet arthritis can result in enlargement of the facet joint which can also compromise the lateral part of the spinal canal, narrowing the nerve window (foramen) and potentially compressing the nerve root. Wear and tear of the facet joints can also, over time, lead to the development of calcified bone spurs which in turn contribute latera canal stenosis.

Lateral Canal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) – LS: Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of lateral canal stenosis develop when it results in the narrowing of the neural formaen (nerve window), and compresses the nerve root. In the absence of nerve root compression, the stenosis per se may not give rise to any symptoms, but there may be pain that reflects the underlying anatomic factors contributing to the stenosis such as disc herniation, facet arthritis etc

See: Disc pain

See: Facet pain

Sciatica

Narrowing of the lateral aspects of the spinal canal can result in narrowing of the nerve windows (foramen) where nerves exit the spinal cord to extend down the legs. When these nerve roots are compressed by a disc or extruded disc contents, enlarged facet joints and/or bone spurs, the pain will typically be perceived as sharp, stabbing, burning or electric shock-like and refer down the leg in a pattern typical for each specific nerve root. Classically, this pattern of nerve pain, or sciatica, typically follows a narrow band (dermatome) and likely extends below the knee and often to the ankle or foot. There are five lumbar nerve roots (L1-5) bilaterally, corresponding to each vertebral level and each level of nerve root supplies a specific set of muscles, sensation to a narrow band of distribution and pain that radiates in this narrow band pattern.

Incidence of lateral foraminal stenosis increases in the lower lumbar levels because of increased dorsal root ganglion (DRG) diameter with resulting decreased foramen (ie, nerve root area ratio). The frequency of commonly involved roots are: L5 (75%), L4 (15%), L3 (5.3%), and L2 (4%). The lower lumbar levels also have a higher incidence of degenerative changes from wear and tear, further predisposing the L4 and L5 nerve roots to compression (impingement).

Patients with lateral stenosis and narrowing of the neural foramen likely have pain that radiates predominantly into the leg or buttock region, often in the distribution of a single dermatome, reflecting the individual nerve root compressed. It may be constant or intermittent and may be positional, triggered for example by bending or twising. While there are many charts illustrating proposed distribution patterns (dermatomes) for each lumbar nerve, studies actually have shown that there is a great deal of individual overlap between these nerves such that individual variations will most likely not match predicted charts, with the exception of the S-1 nerve root that is more consistent.

Pain arising from a compressed (or irritated) nerve root is most reliably characterized by a burning or electric-like pain typical of other nerve pain, but may be described also as sharp, stabbing or even aching. It may be aggravated by coughing, sneezing or a valsalva manouver (straining with a stool) that increases intra-abdominal pressure that further compresses a nerve root.

Lateral Canal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) – LS: Physical Exam

With nerve root compression, decreased reflexes may be evident along with weakness and/or numbness of the lower extremities.

Late

ral Canal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) – LS: Diagnosis

Lateral stenosis can be predicted by findings on routine x-rays but actual nerve root compression visualization requires MRI or CT scan.

Potential confirmation that the visualized stenosis is the cause of pain is at least temporary relief of leg pain after transforaminal epidural blockade of the suspected nerve root.There may be longer relief if corticosteroids are administered (transforaminal ESI). While patients usually experience at least temporary relief of pain after epidural steroid injection and no relief after Medial Branch block (MBB), this is just the opposite of FJ pain.

See: Epidural Injections

See: Nerve Blocks & Radiofrequency Ablations

Lateral Canal Stenosis (Foraminal Stenosis) – LS: Treatment

Successful management of chronic LBP often requires an “interative” approach, that is a treatment regimen that incorporates a multi-disciplinary collection of treatment options that include education, exercise, trigger point therapy, massage, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, diet and nutritional supplements, medications and mind-body disciplines such as yoga and tai chi. These topics are covered elsewhere on this website.

Treatment of lateral canal stenosis is directed more specifically at the underlying cause, i.e. disc pathology, facet arthropathy etc. However, in general, lateral spinal stenosis is treated with flexion-biased body mechanics/exercises. Interventional treatment options include epidural injections and surgical options are directed at decompression (for further information, the reader is directed to a surgeon).

References

LBP: Spinal Stenosis – Overviews

- Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis – a systematic review of the accuracy of diagnostic tests. – 2008

- Spinal Stenosis 2 Clinical Presentation

- Spinal Stenosis And Neurogenic Claudication – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf – 2022

LBP: Central Stenosis – Claudication

LBP: Central Stenosis – Mechanisms of Pain

- The Discriminative Validity of “Nociceptive,” ” Peripheral Neuropathic,” and “Central Sensitization” as Mechanisms-based Classifications of Musculoskeletal Pain – 2011

- Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians – 2010

LBP: Central Stenosis – Treatment

- Pathoanatomical characteristics of clinical lumbar spinal stenosis – 2013

- Nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication. 2013 – PubMed – NCBI

- The MILD Procedure for central spinal stenosis- 2011

- Long-term Outcomes of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis -Eight-Year Results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) – 2015

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an A

ccurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.