Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

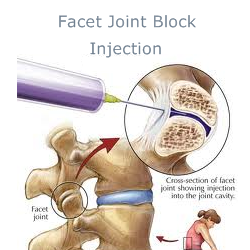

The facet joints connect the posterior aspects of the vertebral bodies to one another. Like other joints, the facet joints can become arthritic and painful. When conservative therapy fails to provide adequate pain relief, the use of interventional procedures may be indicated. These procedures fall into two categories: diagnostic and therapeutic. The facet joint may be injected directly or the nerve transmitting pain sensation may be blocked or ablated (burned).

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

See Also:

Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) JointPain

.

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Root Blocks

The Facet Joint

The facet joints are paired, left and right, at each level of the vertebra in the neck and back. They function to allow movement of the spine: forward, backward, side-to-side and rotational. Like knees and hips, they consist of a joint capsule, articulating cartilage overlying the bone of the joint and they contain synovial joint fluid. Facet joints, especially in the neck, are very susceptible to damage associated with trauma particularly motor vehicle accidents and falls. Also, like other joints, they can develop degenerative changes of wear-and-tear associated with aging and arthritis with the facet joint being the most common source of pain in the neck and back.

When treating neck or back pain it is important to identify the anatomical source of the pain, if possible, in order to guide treatment. When facets in the neck are the source of pain (facetogenic pain), the pain may be perceived in the neck, upper back, shoulder or even as headaches. Facets in the midback or lower back can be the source of local pain in the region of the affected facets, or they may refer pain up or down the spine. Facetogenic pain is often worse when the facets are “loaded,” as when extending the spine backwords or twisting or leaning side-to-side, movements which apply pressure on the articular surfaces within the facet joints that trigger pain.

Due to the lack of reliable findings by history or on physical exam, it can be challenging to identify specific facets as the source of someone’s pain. Even imaging studies such as x-rays, CT scans or MRIs may be suggestive but inconclusive in identifying specific sources of neck or back pain.

Diagnostic Procedures

To accurately identify a facet as the source of pain (facetogenic pain), the most reliable means is to anesthetize (“numb”) the joint. If numbing, or “blocking” the joint successfully relieves the targeted pain, it is believed to reliably identify the joint as the source of pain. That being said, however, even the blocking procedures are not entirely reliable due to variables in placebo response and some degree of inability to accurate reproduce the diagnostic procedure. It is therefore common to not rely on only one positive diagnostic injection, but require a second confirmation block. There still remains controversy regard

ing the interpretation of diagnostic block injections.

There are two types of diagnostic blocks:

Intra-Articular Blocks

Intra-articular facet blocks involve the direct injection of anesthetic into the facet joint under fluoroscopic x-ray guidance. As a control, saline is sometimes injected to help rule out false positive anesthetic injections.

Medial Branch Blocks

The nerves that carry pain signals from the facet joints are the medial branches of the local spinal nerves (the dorsal rami). Injection of a local anesthetic that blocks these nerves, called a medial branch block (MBB) can block pain signals and positively confirm the specific nerve carrying the pain signals. A MBB is commonly used to identify the specific nerve coupled with a suspected facet joint thought to be the generator of pain. However, adjacent structures including the multifidous paraspinal muscles are also innervated by the same medial branch and may also be pain generators.

Medial branch blocks have been shown to be safe. That being said, there is a lack of consensus regarding their interpretation. Some guidelines call for at least two succesful MBBs to confirm accuracy of the diagnosis of facet-generated pain. The degree of pain relief neccesary for a positive response is also a point of contention. At least a 50% or greater reduction of pain is required by some protocols to confirm a positive response, others protocols call for a 75-80% and up to 100% relief of pain for confirmation. In contrast, some argue that a prior MBB is not necessary to proceed to a radiofrequency ablation (see below).

Indications for Facet Joint Injections or Medial Branch Nerve Blocks

(1) To confirm disabling non-radicular low back (lumbosacral) or neck (cervical) pain, suggestive of facet joint origin based upon all of the following:

− (a) history, consisting of mainly axial or non-radicular pain, and

− (b) physical examination, with positive provocative signs of facet disease (pain exacerbated by extension and rotation, or associated with lumbar rigidity).

(2) Lack of evidence, either for discogenic or sacroiliac joint pain; AND

(3) Lack of disc herniation or evidence of radiculitis; AND

(4) Intermittent or continuous pain with average pain levels of ≥ 6 on a scale of 0 to 10 or functional disability; AND

(5) Duration of pain of at least 2 months; AND

(6) Failure to respond to conservative non-operative therapy management.

(7) All procedures must be performed using fluoroscopic or CT guidance.

Recommended Frequency of Facet Blocks:

(1) There must be a minimum of 14 days between injections

(2) There must be a positive response of ≥ 50% pain relief and improved ability to perform previously painful movements

(3) Maximum of 3 procedures per region every 6 months.

(4) If the procedures are applied for different regions (cervical and thoracic regions are considered as one region and lumbar and sacral are considered as one region), they may be performed at intervals of no sooner than 2 weeks for most types of procedures.

(5) Maximum of 3 levels injected on same date of service.

(6) Radiofrequency Neurolysis procedures, also called neurotomies, should be considered in patients with positive confirmation facet blocks (with at least 50% pain relief and ability to perform prior painful movements without any significant pain).

Treatment Procedures

Facet Injections (Intra-Articular Steroid (IAS) Injections)

The facet joints can be selectively injected with a mixture of a local anesthetic and an anti-inflammatory steroid (like cortisone) in the same manner commonly employed for painful, arthritic shoulders and knees. Pain relief can sometimes be significant and last for weeks or even up to 3-6 months but unfortunately, while definitive studies are still lacking to identify accurate response rates, it appears that less than 50% of these procedures provide significant, lasting relief.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) or Radiofrequency Neurotomy (RFN)

If spine pain believed to be arising from facet joints is inadequately controlled by conservative, non-invasive treatment, consideration is given to performing a radiofrequency ablation (RFA). RFA, (sometime also called neurolysis), is a minimally invasive treatment for cervical, thoracic and lumbar facet joint pain, also referred to as a “neurotomy.” It involves using electrical energy in the radiofrequency range to burn specific nerves (medial branches of the dorsal rami), preventing nerve transmission of pain. The goal of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is only to provide relief of pain – it does not correct the underlying problem that lies in the facet as the source of pain. The burning of the nerve is hoped to achieve a significant reduction of pain for up to 6-12 months, possibly up to 18 months.

Used most often for facet joint pain, radiofrequency ablation is now also emerging as a treatment for sacroiliac joint pain. However, at this time there is only limited evidence that it is effective in treating sacroiliac joint pain and is still considered investigational and not medically necessary for this application.

Indications for Facet Joint Denervation (Radiofrequency Neurolysis)

– Positive response to one to two successful diagnostic medial branch blocks (MBB) of the facet joint, with at least 50% pain relief and ability to perform prior painful movements without significant pain, but with insufficient sustained relief; OR

– Positive response to prior radiofrequency neurolysis procedures with at least 50% pain improvement for up to 6 months of relief in past 12 months; AND

– The presence of the following:

(1) Lack of evidence that the primary source of pain being treated is from discogenic pain, disc herniation, radiculitis, or sacroiliac joint pain;

(2) Intermittent or continuous facet-mediated pain (average pain levels of ≥ 6 on a scale of 0 to 10) causing functional disability;

(3) Duration of pain of at least 3 months; AND

(4) Failure to respond to more conservative non-operative management

Recommended Frequency of RFA:

(1) Relief typically lasts between 6 and 12 months and sometimes provides relief for greater than 2 years. Repeat radiofrequency denervation is performed for sustained relief up to two and three times.

(2) Limit to 2 facet neurolysis procedures every 12 months, per region

Effectiveness:

The median time for return of at least 50% of preoperative pain level was found to be 263 days in one recent study. In this study, 87% of patients obtained at least 60% relief of pain and 60% of patients obtained at least 90% relief of pain at 12 months. This procedure has a good safety profile and is commonly employed. However, there have been multiple studies investigating benefit of RFA and outcomes have been mixed, usually based on flaws in the study protocols.

A 2004 study evaluated the effectiveness of repeated RFAs and concluded that repeated precedures remain effective, offering similar benefits to the initial procedure with reduced pain lasting 5-12 months, with a median of 9 months, and considered successful 85% of the time. A recent 2015 study concluded that there was a greater likelihood of long-term improvement in function and pain if the RFA procedure was repeated. Each additional RFA treatment is associated with approximately 10–16 months of improvement in symptoms in patients who received benefit from the first procedure. This study provides support to the feasibility of using appropriately repeated RFA for long-term treatment of lumbar facet syndrome.

Complications: Neuromas

RFAs are generally considered safe with few, but minor complications. Some clinicians have concerns about this treatment of “killing the messenger.” While there is an established benefit of prolonged pain reduction, the concern is regarding the potential for pathologic re-growth of the burned nerve 6-12 months out. Burning a healthy nerve places that nerve at risk for growing back abnormally with the potential for creating a neuroma, yet another pain generator with the regenerated nerve.

Traumatic neuromas are rare but painful lesions that occur at the proximal end of a severed nerve. They are not true neoplasms but hyperplastic proliferations of neuronal and fibrous connective tissue that occur in response to nerve injury. Neuroma formation is well known following chemical, surgical, and cryoablation neurolysis; however, it is thought to be rare with radiofrequency ablation. When this problem does develop, however, treatment options are limited. Further radiofrequency ablations may not only be ineffective but may cause further injury. A potential treatment option would be a minimally invasive open surgical ablation/neurectomy of the neuroma using three-dimensional, fluoroscopy-based image guidance.

A traumatic neuroma may present as a different type of pain than the original facetogenic pain, which is usually of nociceptive character: often dull, achy and indistinctly localized. Neuroma pain is neuropathic, and likely to be progressively more sharp, electric or burning in character and associated with focal allodynia and hyperalgesia.

Conclusions

In 2013, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) released an update of their guidelines for interventional techniques in patients with chronic spinal pain. The guidelines state that evidence for the therapeutic effectiveness of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks is fair to good but that there is only limited evidence for the effectiveness of intra-articular lumbar facet injections. The ASIPP guidelines also state that there is good evidence for the therapeutic effectiveness of RF ablation in lumbar facet joint interventions.

References

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management, American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine: Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologist Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology 2010; 112(4):810-33.

Facet Pain – Interventional Procedures (IP)

- An Update of Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines for Interventional Techniques in Chronic Spinal Pain. Part I Guidance and Recommendations – 2013

- An Update of Comprehensive Evidence-Based Guidelines for Interventional Techniques in Chronic Spinal Pain. Part II Guidance and Recommendations – 2013

- Paraspinal Injections – Facet Joint and Nerve Root Blocks -2014

- 2016 NIA clinical guidelines

IP – Radiofrequency Ablations (RFA)

- Long-Term Function, Pain and Medication Use Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Lumbar Facet Syndrome – 2015

- The significance of multifidus atrophy after successful radiofrequency neurotomy for low back pain. – PubMed – NCBI

- Effectiveness of repeated radiofrequency neurotomy for lumbar facet pain. – PubMed – NCBI

- Clinical predictors of success and failure for lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. – PubMed – NCBI

IP – Radiofrequency Ablations – Neuromas

- Painful medial branch neuroma treated with minimally invasive medial branch neurectomy. 2010 – PubMed – NCBI

- Success of initial and repeated medial branch neurotomy for zygapophysial joint pain: a systematic review. 2012 – PubMed – NCBI

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.