“Men succeed when they realize that their failures are the preparation for their victories”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

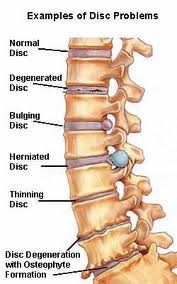

Low Back Pain: Discs

Chronic low back pain is usually multifactorial, but the intervertebral disc is estimated to be the most common source of chronic LBP, estimated by authorities to be the source in about 40% of LBP cases. Like other anatomic sources of LBP, there are patterns and characteristics of pain and imaging findings that can help identify the disc as a pain generator. Surgical and interventional procedures are also available for managing discogenic pain. There are common misconceptions regarding disc pain, especially that the presence of a “bulging” disc on an MRI of the lumbar spine represents a definitive source of pain.

See Also:

Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

LBP – Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

LBP – Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

LBP – Surgery:

.

Low Back Pain – Disc pain

The spine consists of bony elements, the vertebrae, that are separated from one another by discs that function as shock absorbers to prevent damage from bone-against-bone trauma related to movement of the spine. Healthy discs are elastic, that is they return to their regular shape after be compressed during movement of the spine like an elastic, or rubber, band does after being stretched. The intervertebral discs are composed of a central gelatinous-like core, or “nucleus pulposus” containing water and glycogens that are surrounded by a restraining laminated ligamentous (fibrous) covering or “annulus.”

In the normal disc the superficial layers of the fibrous capsule, or annulus, have sensory nerve endings that may potentially generate pain. In painful discs it is believed that these nerve endings become sensitized and thereby respond to innocuous, normally non-painful stimuli with pain, such as sitting for prolonged periods.

The Evolution of Disc Pain

As we age, our discs dehydrate (“dessicate”) which makes them more susceptible to injury as a consequence of losing their elasticity. The use of tobacco and nicotine products can markedly accelerate the dehydration of discs by impairing the disc’s blood supply, as provided by small blood vessels that are susceptible to the drug effects. Thus, while many factors contribute to risk for disc injury and associated chronic back pain, including family history, use of tobacco is a significant contributor that can be eliminated.

Through the daily wear and tear of bending at the waist, lifting heavy objects or the trauma associated with forceful flexion such as occurs in motor vehicle accidents, discs can bulge, tear or herniate. A bulging disc is a common finding in patients both with and without back pain and is not considered, by itself, a likely argument for pain.

If the fibrous capsule around the disc is disrupted, or torn, fissures can form and depending on the extent in which they penetrate into the disc, inflammatory chemicals or mediators, can leak out that can be irritating to surrounding tissues including nerve roots, causing pain.

In the case of the most severe disruption of the disc, hernation, the contents of the disc can leak out, or extrude, into the spinal canal triggering inflammation and pain. That being said, however, even disc herniations can be demonstrated on MRIs of patients with no back pain. Leakage of contents from a herniated disc may include inflammatory chemicals such as phospholipid A or actual gelatinous contents, the nucleus pulposis of the disc. Symptomatic herniated discs are present in about 4% of patients with low back pain. About 90% of disk herniations resolve spontaneously and in more than 70% of disk herniations, extruded disk material resolves on its own, given enough time; however, this process can take well over a year.

When discs significantly bulge, herniate or extrude posteriorly in the midline, however, they can impair the flow of spinal fluid by narrowing the spinal canal, a potentially painful condition called central spinal stenosis (stenosis means narrowing). Spinal stenosis is present in about 3% of patients with low back pain.

If the disc or contents extend even further posteriorly, it can compress the spinal cord leading to potential pain along with dysfunction of the spinal cord causing a condition, Cauda Equina Syndrome. The Cauda Equina Syndrome is most commonly associated with massive midline disc herniation but is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 0.04% among patients with low back pain.

If the disc bulges laterally, it can also compress the nerve roots, the bases of the nerves that leave the spinal cord at each verterbral level, left and right, and exit through a nerve window or neural foramen. When a nerve root is compressed by a bulging disc, bone spur or other element, it can be a source of pain, characteristically giving rise to a “radicular” pain that distributes a pattern of pain particular for each nerve root and in the lumbar area it may be referred to as “sciatica.” In addition to pain, a compressed nerve can also give rise to numbness and/or weakness as well, a triad of symptoms referred to as a “radiculopathy,” again in a distribution particular to each individual nerve root. Thus, in addition to causing low back pain, a herniated disc can cause a constellation of symptoms if it affects the nerve roots as well.

Symptoms of Disc Pain (Discogenic Pain)

A typical presentation for discogenic LBP is usually dominant midline pain that frequently radiates to the left and right of the midline, the buttocks (gluteal regions), and may radiate to the leg in a nonspecific (nondermatomal) pattern. Discogenic pain is usually worse sitting and during transition from sitting to standing. It may improve with standing or walking and worsen with forward flexion at the waist.

Compared with LBP arising from facet joints and SI joints, discogenic pain is more likely in younger patients and less likely as patients age.

In the absence of nerve root irritation or compression, discogenic pain is likely to be described as dull, throbbing or aching. When there is nerve root irritation or compression, it is likely to be typical of nerve pain (neuropathic pain) and perceived as sharp or stabbing, burning or electric and typically radiates down the leg in a narrow band, usually to the lower leg and/or foot in what is referred to as a dermatomal pattern. While there are charts mapping out expected dermatomal patterns for nerve roots at each level, in reality the referrral pattern

may not match the charts. In the case of the S-1 nerve root, however, the predicted pattern of involvement of the small, 5th toe is generally reliable.

Physical Examination for Discogenic Pain

There are no findings on static physical examination that will reliably diagnose discogenic pain. However, a dymamic evaluation of low back pain that elicits centralization or peripheralization suggests a strong likelihood of discogenic pain whereas a lack these findings is more likely to identify non-discogenic sources of pain such facet or sacro-iliac pain.

“Centralization” and “peripheralization” occur commonly during dynamic, mechanical assessment of patients with low back pain, using repeated end-range lumbar test movements. The most distal extent of the referred or radicular pain, even if the pain has only spread as far as the lateral back, rapidly recedes toward and/or to the lumbar midline with centralization. Midline pain can also rapidly abolish under these same testing circumstances, by a single direction of repeated end-range movements. In other words, centralization of pain is the progressive retreat of the most distal extent of referred or radicular pain toward or to the lumbar midline. Peripheralization is the oppositely directed phenomenon.

The most common direction of lumbar testing that centralizes pain (directional preference) is extension, whereas a smaller number will centralize only with laterally directed movements. A much smaller number will centralize and abolish with lumbar flexion only.

Furthermore, centralization is most consistent with discogenic pain associated with an intact fibrous (annular) capsule and predicts greater likelihood of earlier recovery and reduced pain over time. Peripheraliztion, on the other hand, is most consistent with disruption of the annular capsule as found with herniated discs, especially those with accopanying extrusion of disc contents. Peripheraliztion also predicts greater disability and correlates with a poorer prognosis.

Dynamic Internal Disc Model

As a means of explaining why centralization and peripheralization occur, McKenzie proposed that the direction of bending that centralizes the pain precisely corresponds with the direction in which disc nuclear content has abnormally migrated, generating referred symptoms by mechanically stimulating the anulus or nerve root. As long as the anulus and the hydrostatic disc mechanism are intact, however, an offset load on the disc in the lesion-specific direction of spinal bending can apply a reductive force on the displaced nuclear content, directing it toward its original central disc location. Such a reduction of displacement would alleviate stress on the symptom-generating anulus and/or nerve root, thereby centralizing and/or abolishing the pain, and identifying the patient’s (or lesion’s) “directional preference.”

For displaced nuclear content that is symptom-producing to respond to an asymmetric load in a reductive/pain-centralizing fashion, the hydrostatic mechanism must be functional, and the nucleus must be contained within an intact anular envelope. However, if no centralizing direction is found during spinal testing, and if multiple directions of testing only peripheralize the distal pain, this dynamic internal disc model theorizes that the anulus is incompetent and the hydrostatic mechanism nonfunctional. This explains the basis of why patients with extruded discs were noncentralizers/peripheralizers when assessed mechanically.

Imaging Finding for Discogenic Lumbar Pain

X-rays of the Lumbar Spine

Discs are not visualized by x-rays of the spine, so no information regarding the integrity of the disc can be determined. However, in the case of significantly degenerated discs, they shrink in size and the distance between the adjacent vertebrae can be seen to be lessened along with the possibility of visualizing narrowed neural foramen.

CT Scans (“CAT Scans) of the Spine and Discogenic Pain

CT scans provide good information about bones and the “soft tissues,” such as discs, ligaments and other structures. While they are not quite as informative as an MRI for the soft tissues, they are superior to an MRI for evaluating bone. This may be important when assessing trauma to the spine and looking for fractures. Unfortunately, CT scans generate radiation that can be toxic when accumulated over time and should be used cautiously.

MRI Scans (“Magnetic Resonance Imaging” Scans) of the Spine and Discogenic Pain

MRI scans also provide information about bones, but are superior to CT scans for evaluating the “soft tissues,” such as discs, ligaments and other structures. Unlike CT scans, MRIs do not generate any dangerous radiation but because their techonology is based on magnetism, they are susceptible to artifacts from iron-based metals that may interfere with accurate imaging.

Findings on an MRI that suggest the disc to be a pain generator include the presence of fissures in the annular capsule. The fissures are graded in severity and the greater the fissure penetrates the disc, the stronger is the likelihood of pain. Radial fissures are the hallmark of internal disc disruption and the finding of radial fissures is consistent with internal disc disruption and discogenic pain.

Another feature that suggests the disc is a pain generator is signal changes in the bone marrow adjacent to a vertebral endplate, known as Modic changes. Modic type-I changes represent edema (swelling) in the bone marrow, and are evident on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images (different MRI measures). Modic type-2 changes represent fatty infiltration in the marrow, and are best seen on T1weighted images. Sequentially in time, these changes imply an acute and then chronic inflammatory response to an injury to the disc. These changes are strongly related to the affected disc b

eing painful. Modic changes have low sensitivity but their specificity and likelihood ratios are very high – which means their absence doesn’t argue strongly for lack of pain but their presence is good evidence for pain.

Discography (Discograms)

Lumbar discography is a procedure designed to determine if a lumbar intervertebral disc is the source of back pain. If supplemented by postdiscography CT scan using contrast, it may identfy internal disc disruption thought to be consistent with discogenic pain.

The therapeutic benefit of lumbar discography still remains unproven. Studies have not yet confirmed that any treatment can reliably and consistently relieve pain if directed at a disc found to be symptomatic by discography.

Treatment of Discogenic Lumbar Pain

The successful diagnosis and treatment of discogenic pain has been frustrating and variable. While many patients respond well to conservative management, about 5% of patients with a component of discogenic pain will have persistent pain. Different therapies, including lumbar fusion, disc replacement, epidural steroid injection therapies, and thermal annular procedures (TAPs) have been performed. There is considerable controversy over the effectiveness of any of these procedures. Surgical procedures are associated with high morbidity (high complication rate), so alternative treatments are usually sought.

Treatment Based on Mechanisms of Discogenic Pain

Discogenic pain may be a result of different mechanism of pain, including nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic and central sensitization (See Neurobiology of Pain). When the source of pain is limited to disruption of the disc capsule, the pain is likely related to inflammation and nociceptive factors and would be consistent with the pain experience to be dull, aching and throbbing. In this circumstance medical management may focus on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and, when severe, opioids. There may be a role for CAM treatment directed at inflammation (See CAM – Osteoarthritis),

In the case of herniated discs associated with nerve root irritation and/or compression, especially coupled with symptoms of radicular pain (sciatica), especially when the pain is experienced as sharp, stabbing, burning or electric-like, medical management may focus on agents directed at neuropathic pain (See Neuropathic Pain).

It has been established that chronic LBP can be associated with central sensitization. When symptoms are constant and disruptive to quality of life and the painful experience includes hyperalgesia, allodynia and other sensory sensitivity, treatment should also be directed at central sensitization (See Central Sensitization).

Physical Therapy

The benefit of physical therapy has been well established for discogenic pain but must be individually assessed and directed. Clinical studies support use of the McKenzie method as being effective in patients with discogenic back pain. MRI studies have revealed that prolapsed or bulging disc regress during McKenzie’s repeated back extension exercises. Similar reductions have been observed with the preactice of yoga.

See Physical Therapy

Epidural injections

Epidural injections are used in managing spinal pain secondary to discogenic pain, disc herniation, spinal stenosis, postsurgery syndrome and other conditions. In general, ESIs are directed at the treatment of symptoms and not based on MRI findings. A 2011 study showed that MRI findings do not predict success of ESIs.

Epidural injections are one of the most commonly performed non-surgical treatments for LBP. However, their extent of effectiveness in managing low back pain and lower extremity pain has been controversial. Several studies and systematic reviews have been conducted recently to assess the benefits of epidural injections and it appears there is now high quality evidence to support the likelihood of benefit for multiple LBP conditions, including lumbar discogenic pain and lumbar radicular pain associated with disc herniation.

Thermal Annular Procedures (TAPs)

Since nerve ingrowth and tissue regeneration in the annulus is felt to be the source of pain in discogenic low back pain, procedures were developed using heat to restructure the annulus and reduce pain. One theory as to the goal of the application of heat across the damaged annulus is to destroy the nerves in the annulus, leading to pain relief. An alternative theory is that the heat reconfigures the structure (collagen) of the annulus, but the actual mechanism is unclear.

Thermal annular procedures (TAPs) were first developed in the late 1990s in an attempt to treat discogenic pain and potentially provide greater ef

fectiveness with fewer complications and at a lesser cost than fusion surgery. Three technologies have been developed that apply heat to the disc annulus: intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET), discTRODE, and biacuplasty.

When describing these three techniques, the term “thermal annular procedures” is used rather than “thermal intradiscal procedures.” Studies treating the nucleus are still eperimental. TAPs have been the subject of significant controversy. Multiple reviews have been conducted resulting in varying conclusions.

Intradiscal Electrothermal Therapy (IDET)

As of 2012, IDET was evaluated in limited number of studies andthe evidence supporting the efficacy of IDET is “weakly fair.” IDET may be effective with short-term (6 months) benefit of discogenic pain, however, the evidence is limited.

While some serious complications have been reported and are considered “rare,” there are no published frequency data of these complications.

Reported complications include catheter breakage, nerve-root injuries, post-IDET disc herniation, cauda equina syndrome, infection, epidural abscess, and spinal cord damage. Up to a 10% complication rate has been noted but the majority of these complications were transient, generally minimal and self-limited. The procedure is considered low risk for serious adverse events.

discTRODE

As of 2012, there was only one study evaluating discTRODE and it showed no benefit from the procedure; therefore, while the evidence is limited, it is considered “poor.”

Biacuplasty

There is insufficient evidence to rate the effectiveness of biacuplasty for treating low back pain. Therefore, the evidence is “poor.”

Surgical Treatment of Disc Pain

The surgical management of disc pain is beyond the scope of this website and the reader is referred to expert orthopedic or neurosurgical spine surgeons for definitive information. In this writer’s opinion, however, surgery specifically for pain should almost always remain as the last option in pain management, to be considered only when conservative therapies fail. No surgical procedure can guarantee resolution of pain and many surgeries come with the potential for significant complications, including the worsening of pain.

On the other hand, when there are functional impairments and/or the potential for compromised spinal cord function, surgical procedures should be considered. In all cases, the benefits should outweigh the risks and should be carefully discussed with the surgeon prior to engaging.

Surgical procedures engaged for disc pathology include lumbar spinal fusions and artificial disc replacements. In the surgical management of lumbar disc herniation (LDH), arguably the main cause for radicular pain, it has been estimated to lead to failure in approximately 25% of patients, even in well-selected cases.

Future Treatment Possibilities

Biologic Therapy

Research is ongoing to evaluate strategies directed at regenerating the cellular matrix inside dessicated discs and restoring healthy function and reducing inflammation. Early animal experimental efforts have included the transplantation of disc material and have provided limited benefits. Human studies involving reimplantation of cultured cells into the center of dessicated discs have also been promising. Stem cell implantation is getting a great deal of interest and may offer promise.

References

LBP: Disc Pain – Overviews

- The reliability of clinical judgments and criteria associated with mechanisms-based classifications of pain in patients with low back pain disorders – 2016

- Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain – Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? – 2009

- Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy – 2013

- Multivariable Analysis of the Relationship between Pain Referral Patterns and the Source of Chronic Low Back Pain – 2012

- A Prospective Study of Centralization of Lumbar and Referred Pain – A Predictor of Symptomatic Discs and Anular Competence – 1997

- Clinical examination findings as prognostic factors in low back pain – a systematic review of the literature – 2015

LBP: Disc Pain – Physical Therapy

- LITERATURE REVIEW ON PERTINENT Imaging Findings for Discogenic Back Pain – 2015

- Lumbar disk prolapse – Response to mechanical physiotherapy in the absence of changes in magnetic resonance imaging. Report of 11 cases – 2008

LBP: Disc Pain – Mechanisms of Pain

- The Discriminative Validity of “Nociceptive,” ” Peripheral Neuropathic,” and “Central Sensitization” as Mechanisms-based Classifications of Musculoskeletal Pain – 2011

- Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians – 2010

LBP: Disc Pain Tx – Epidural Injections

- Epidural injection with or without steroid in managing chronic low back and lower extremity pain – a meta-analysis – 2015

- Comparison of the efficacy of saline, local anesthetics, and steroids in epidural and facet joint injections for the management of spinal pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials – 2015

- A Prospective Evaluation of Complications of 10,000 Fluoroscopically Directed Epidural Injections

LBP: Disc Pain Tx – Future Approaches

LBP: Disc Pain Tx – Thermal annular procedures (TAPs)

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.