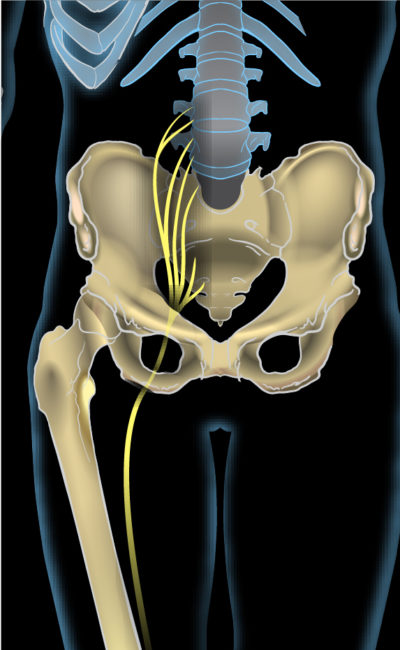

The lumbosacral spinal nerves joining to become the sciatic nerve

“The greatest evil is physical pain”

– Saint Augustine

LBP: Sciatica

“Sciatica” is a term that is commonly used but confusing in that for most researchers and clinicians, it refers to a “radicular” pain, defined as originating from compression, inflammation or irritation of a nerve root in the lumbosacral spine that results in a specific pain that radiates down the leg in predictable manner based on the nerve root(s) involved.

Many clinicians and patients alike, however, have come to apply “sciatica” to any pain that originates in the back and refers down the leg. Because there are many sources of back pain that refer down the leg, not all of which are “radicular,” it becomes evident that there is a problem in communication. Without a consensus of definition, the term becomes less meaningful and therefore more difficult if not impossible to evaluate.

For the purpose of this website, the term “sciatica” is used to describe sciatic pain that originates in the lower back and travels through the buttock and down the leg, following the distribution of the sciatic nerve. Sciatic pain arises from a compressed (or irritated) nerve root and is usually characterized by a burning or electric-like pain, but may be described also as sharp, stabbing, tingling or even aching. It is usually a consequence of severe lateral spinal stenosis that leads to compression of nerve roots exiting the spinal cord. It may be aggravated by coughing, sneezing or a valsalva manouver (straining with a stool) that increases intra-abdominal pressure that further compresses a nerve root.

Other sources of referred pain from the back down the leg include an inflamed or damaged disc (unrelated to nerve compression), facet joints and muscles in the back (myofascial pain or trigger points). It is important to distinguish the source of referred pain, sciatica or otherwise, to effectively establish a treatment plan. The evaluation of referred pain is difficult, however, because of the significant overlap in patterns generated by the many different sources. These patterns are discussed below and the web pages noted here, specific to each diagnosis.

See Also:

Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

LBP – Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

LBP – Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

Treatment Medications:

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

LBP – Surgery:

.

LBP: Sciatica and Other Pain Referred down the Leg

Sciatica

Narrowing of the lateral aspects of the spinal canal can result in narrowing of the nerve windows (foramen) where nerves exit the spinal cord to extend down the legs. When these nerve roots are compressed by a disc or extruded disc contents, enlarged facet joints and/or bone spurs, the pain will typically be perceived as sharp, stabbing, burning or electric shock-like and refer down the leg in a pattern typical for each specific nerve root.

Classically, this pattern of nerve pain, or sciatica, typically follows a narrow band (dermatome) and likely extends below the knee and often to the ankle or foot. There are five lumbar nerve roots (L1-5) bilaterally, corresponding to each vertebral level and each level of nerve root supplies a specific set of muscles, sensation to a narrow band of distribution and pain that radiates in this narrow band pattern. The two lower segments (L3-L4 & L4-L5) of the lumbar spine, because they provide the most motion, are most commonly affected by degenerative stenosis.

Incidence of lateral foraminal stenosis increases in the lower lumbar levels because of increased dorsal root ganglion (DRG) diameter with resulting decreased foramen (ie, nerve root area ratio). The frequency of commonly involved roots are: L5 (75%), L4 (15%), L3 (5.3%), and L2 (4%). The lower lumbar levels also have a higher incidence of degenerative changes from wear and tear, further predisposing the L4 and L5 nerve roots to compression (impingement).

Patients with lateral stenosis and narrowing of the neural foramen likely have pain that radiates predominantly into the leg or buttock region, often in the distribution of a single dermatome, reflecting the individual nerve root compressed. It may be constant or intermittent and may be positional, triggered for example by bending or twising. While there are many charts illustrating proposed distribution patterns (dermatomes) for each lumbar nerve, studies actually have shown that there is a great deal of individual overlap between these nerves such that individual variations will most likely not match predicted charts, with the exception of the S-1 nerve root that is more consistent.

For more information regarding the causes and treatment of sciatica, see:

Other Leg Pain Referred Down the Leg

Disc Pain (Discogenic)

While pain originating from a lumbar disc and radiating down the leg is most often a result of the disc (or its extruded contents related to herniation) irritating or compressing a nerve root as noted above. However, an injured or inflamed disc is also believed to refer pain as well. The referral pattern for discogenic pain is usually thought to radiates laterally, away from the midline of the lumbar spine but it is also believed to radiate into the buttocks, groin or thigh. It is not thought to commonly, if ever, radiated distal to the knee. Pain originating in the disk is more likely to be described as a deep, dull and aching pain with indistinct margins, but may have sharp and stabbing elements as well. Discogenic pain is likely to be an uncommon source of referred pain outside of the lumbar area however.

For more information regarding the causes and treatment of disc pain, see:

Facet Pain (Facetogenic)

Referred pain from a facet joint is a common finding. While it is classically believed to be limited to referral patterns that do not extend past the knee, studies have shown that it can extend to the calf and, probably rarely, to the foot. It commonly refers to the buttocks area with indistinctly defined margins and into the posterior thighs. It is frequently described as dull and achy or pressure-like, often unilateral. Facetogenic pain is also noted to be associated with stiffness and aggravated by rest and hyperextension, but relieved by repeated motion.

For more information regarding the causes and treatment of facet pain, see:

Myofascial Pain

Myofascial pain is pain derived from muscle and fascia, the fibrous membrane surround muscle and other tissues. It may likely be the most common source of referred pain from the lumber area, The referred pain from muscle is generated by focal areas in the muscle called “trigger points” (TrPs) and the particular referral pattern is predicted by the location of the TrP. An extensive documentation of different TrP referral patterns has been published but some of the most common TrPs in the lumbar area refer to the buttocks and proximal and lateral thigh. However, depending on TrP, the referral pattern can also include abdomen, groin and anterior thigh. Like the referred pain from source other that nerve roots, the pattern of distribution of re

ferred pain is likely to have indistinct margins. It can be aching, stabbing or dull, but may also be burning in character.

For more information regarding the causes and treatment of sciatica, see:

Other Sources of Referred Pain

While it would be exhaustive to attempt to identify every source of referred pain to the lower extremities, it would be misleading to limit the list to discs, facets and myofascial tissues. Ligaments may be a source of referred pain though they have been less studied or understood. Visceral organs can refer pain as well, including the kidneys and ureters and associated kidney stone obstruction which can refer pain to the back and groin, though not likely to the legs. Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta can radiate into the back, buttocks and groin. An infectious source of pain such as herpes zoster (shingles) refers pain that may mimic radicular pain because it also follow a specific nerve distribution and is most often unilateral. Shingles is typically associated with the presence of a typical rash with blisters but the pain can proceed the rash and in some case present without a rash.

Conclusion

It is important to understand that all pain from the back that refers to the lower extremities is not necessarily “sciatica.” It is also important to understand that “abnormalities” noted on an MRI or CT scan of the lumbar spine do not necessarily reflect a definitive source of pain. Identifying a source of LBP and/or its referral pattern requires a thorough assessment. Even with a thorough assessment, unfortunately, a specific, reliable diagnosis may be elusive due to the significant overlap of pain patterns between anatomic sources coupled with extensive individual variatitons.

References

LBP: Sciatica – Overview

- Sciatica. – PubMed – NCBI

- Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain – Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? – 2009

- Neurological examination of the peripheral nervous system to diagnose lumbar spinal disc herniation with suspected radiculopathy – 2013

- Multivariable Analysis of the Relationship between Pain Referral Patterns and the Source of Chronic Low Back Pain – 2012

LBP: Sciatica – Mechanisms of Pain

- The Discriminative Validity of “Nociceptive,” ” Peripheral Neuropathic,” and “Central Sensitization” as Mechanisms-based Classifications of Musculoskeletal Pain – 2011

- Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians – 2010

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.