“The greatest evil is physical pain.”

― Saint Augustine

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM):

Naltrexone for Pain

Hyperalgesia

Hyperalgesia is an exaggerated, increased painful response to a stimulus which is normally painful.

Also see:

- Opioids

- Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

- Withdrawal-Induced Hyperalgesia (WIH)

- Opioid Tolerance

- Neurobiology of Pain

- Neuropathic Pain

- Gabapentin (Neurontin) & Pregabalin (Lyrica)

Definitions and Terms Related to Pain

Key to Links:

- Grey text – handout

- Red text – another page on this website

- Blue text – Journal publication

Links on this Page

Naltrexone – The Old and The New

Naltrexone – History of Use

Naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) is a semi-synthetic opioid developed in the 1960s as an alternative to naloxone for opioid addiction treatment. It was first approved by the FDA in 1984 for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) and subsequently approved for alcohol dependency in 1994. It is prescribed for these conditions in the range of 50 to 100 mg per daily dose. Because its drug safety profile is well established, naltrexone can also be considered for other clinical conditions.

Recently, the use of naltrexone in pain management has gained important attention as an alternative means of treating certain pain conditions otherwise resistant to good pain control, including opioid induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and fibromyalgia amongst other conditions.

Naltrexone for Pain Management

Naltrexone is structurally and functionally similar to the opioid antagonist naloxone (Narcan), but it has a longer half-life and better bioavailability. It is an opioid antagonist that blocks the analgesic and euphoric effects of opioids.

Naltrexone exhibits an uncommon biphasic dose response: it works differently at high doses than at low doses. Consequently, low-dose naltrexone (LDN) in doses ranging from 1 to 5 mg work provides anti-inflammatory effects that reduce pain and central sensitization. Ultra low dose naltrexone (ULDN), doses below 0.01 mg, provides a unique mechanism that higher doses do not provide.

Peripheral Neuropathy

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) shows some evidence of efficacy in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and small fiber neuropathies associated with fibromyalgia, but evidence for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and other small fiber neuropathies is limited and largely anecdotal.

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy:

A single randomized controlled trial found that LDN was as effective as amitriptyline for painful diabetic neuropathy, with a superior safety profile. In this study, LDN significantly reduced pain by 44% in neuropathic conditions, supporting its potential as an alternative or adjunct to standard therapies in diabetic neuropathy.[1][2] However, this evidence is based on a single RCT and retrospective data, so the strength of recommendation is moderate (SOR B).

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy:

There is currently no high-quality randomized controlled trial evidence for LDN in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Most available data are from case series or broader reviews of chronic pain, which mention therapy-related neuropathy as a subset but do not provide robust, condition-specific efficacy data.[3][2] Thus, the evidence for LDN in this indication is weak and primarily anecdotal.

Small Fiber Neuropathy (including Fibromyalgia-associated):

For small fiber neuropathy associated with fibromyalgia, LDN has been studied more extensively. Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses show that LDN is superior to placebo for pain reduction in fibromyalgia, with effect sizes in the small-to-moderate range.[4][5][6] LDN also appears to improve quality of life and other symptoms in some patients, though not all studies reach statistical significance, and the overall strength of evidence is moderate. The mechanism is thought to involve modulation of neuroinflammation and glial cell activity.[7][8][9] However, the most recent large RCT did not find a statistically significant difference in pain reduction compared to placebo, though some secondary outcomes (such as memory) may improve.[6]

Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

Another therapeutic benefit of naltrexone that has been gaining momentum in the last few years is the potential for naltrexone at low doses (LDN: <5 mg) or very low doses (VLDN: < 1 mg) to reduce pain in opioid induced hyperalgesia (OIH), a condition that affects a small but significant number (prevalence estimates vary, but may amount to 5-15%) of patients who take opioids for chronic pain.

Treating OIH is rewarding but it can be somewhat complex so it requires a basic understanding of the nature of OIH to engage treatment.

In this condition, long-term or high dose use of opioids results in a paradoxical effect in which the opioid receptor changes it’s analgesic response, at least partially, to a hyperalgesic response that increases pain. In other words, in addition to reducing pain, the use of opioids in this condition also increases pain at the same time due to the fact that some receptors are now increasing pain and others are decreasing pain by the opioid attachment to its receptor.

This complex process leads to difficulty in controlling pain because increasing the opioid dose does not necessarily provide adequate increased pain control, and may in fact actually make the pain worse. Usually, it just doesn’t allow for the anticipated pain benefit response associated with increased opioid dosing and leaves the patient with continued sub-optimal pain control.

In some cases, OIH may respond to reduced opioid dosing or discontinuation of opioid management. Unfortunately, reducing opioid dosing may not provide optimal pain control and discontinuing opioids may not be tolerated. There is no satisfactory treatment for OIH at this time, but there are two options that offer promise in improving or resolving this dilemma.

One option for treating OIH is to rotate the patient from their prescribed opioids to buprenorphine, a partial agonist opioid that has been shown to reduce OIH while providing significant analgesic benefits. By reversing the OIH induced by the opioids, rotation to buprenorphine usually matches or exceeds the existing level of analgesia the patient experienced on their full agonist opioids. The process of rotating to buprenorphine is generally well tolerated with a protocol using a microdose rotation to buprenorphine. (See: handout).

Low Dose Naltrexone (LDN)

The other option that can be successful in reducing OIH is through supplementing current prescribed opioid management with a low dose (LDN) or very low dose (VLDN) naltrexone regimen. When using naltrexone at these low doses, it does not block the analgesic benefit achieved by the current opioid management, but does reduce pain further through other mechanisms that also provide anti-inflammatory effects and reduction of central sensitization. LDN is thought to improve pain tolerance by restoring the body’s natural endogenous opioid tone as well as helping maintain opioid receptors in normal analgesic mode.

The Nature of OIH

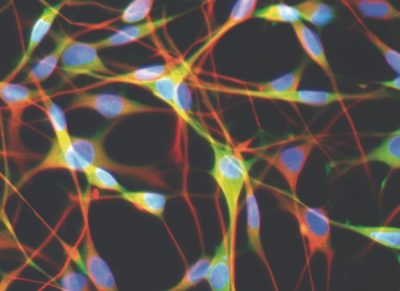

There are two types of opioids, endogenous opioids that are internally sourced, manufactured by the body, and exogenous opioids that are externally sourced, ingested or otherwise introduced into the body. Opioids act on different opioid receptors (mu, kappa, delta), but the one receptor most responsible for providing pain benefit (analgesia) is the mu opioid receptor (MOR) which is a GPCR (G-protein-coupled receptor).

A GPCR is a type of receptor on a cell’s surface that, when activated by opioids or neurotransmitters, interacts (couples) with a G protein which then initiates a signaling process inside the cell that leads to a cascade of events. These events produce effects like pain relief by activating intracellular pathways, leading to the cell transmitting signals to other nerves.

Different G proteins, however, can have significantly different, even opposite, effects when activated. For example, in the MOR, activating the Gi protein results in reduced pain (analgesia) while activating the Gs protein results in increased pain (hyperalgesia). The MOR can couple with multiple different G proteins at the same time, contributing to the complexity of treating the process.

Under normal conditions, the body’s endogenous opioids maintain MOR receptors in the analgesic mode, coupled with the Gi protein subtype which results in reduced pain (analgesia). When the MORs are exposed to high-dose or prolonged exogenous opioids, either by a direct effect or because the endogenous opioids can no longer maintain all the MOR receptors in analgesia mode, some MOR receptors shift to hyperalgesia mode. It is this shift in coupling that leads to opioid-induced hyperalgesia (increased pain sensitivity) as well as the development of tolerance and dependence.

LDN and ULDN (Low Dose and Ultra-Low-Dose Naltrexone) for OIH

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) and ultra-low-dose naltrexone (ULDN) show promising evidence for effectiveness in the management of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), primarily by restoring endogenous opioid tone and modulating neuroinflammation, as well as selective blockade of excitatory opioid receptor signaling.. Standardized protocols are still evolving and high-quality randomized controlled trials are limited.

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) and ultra-low-dose naltrexone (ULDN) treat opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) through overlapping but distinct mechanisms, with evidence supporting both restoration of endogenous opioid tone and modulation of neuroinflammation, as well as selective blockade of excitatory opioid receptor signaling.

Evidence for Effectiveness:

LDN (typically 1–4.5 mg/day): An open-label case series in patients with OIH demonstrated that LDN significantly improved pain tolerance, as measured by the cold pressor test, with pain tolerance more than quadrupling after treatment. The impact was large, and the improvement was statistically significant suggesting LDN can reverse OIH in patients on chronic opioid therapy.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of LDN in chronic pain syndromes, including OIH, fibromyalgia, and other pain conditions, consistently report improvement in pain severity, hyperalgesia, and quality of life. However, most studies are small, mixed in nature and not specific to OIH, some more research is needed.

How LDN works:

- The proposed mechanisms are (1) restoration of endogenous opioid tone and (2) it also reduces neuroinflammation by inhibiting microglial activation and blocking Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling, which reduces central sensitization and hyperalgesia[1] See below for more information regarding the role of endogenous opioid tone in OIH.

- Clinical reviews and meta-analyses support the use of LDN for various pain conditions, including OIH, but emphasize the need for more research to establish effectiveness and optimal dosing.[4][5][6]

- Protocols: Most clinical protocols use oral doses of 1–4.5 mg once daily, typically starting at 1 mg and titrated up by 1 mg every 1–2 weeks based on tolerability and response. LDN is usually continued for several weeks to months, with clinical improvement often seen within 2–8 weeks.[1][7][8]

- Side effects: Mild, transient, (e.g., vivid dreams, headache) |[1][4][5][7][8][6]

ULDN (nanogram doses, <1 mg): Preclinical studies show that ULDN, when co-administered with opioids, reduces hyperalgesia, enhances opioid analgesia, and reduces tolerance. In animal models, ULDN prevents maladaptive mu-opioid receptor signaling and neuroinflammation associated with OIH.

- ULDN prevents and blocks the shift in mu-opioid receptor signaling from inhibitory (Gi) that reduces pain to excitatory (Gs) that increases pain and is associated with OIH. ULDN also blocks TLR4-mediated neuroinflammation (see below), further reducing hyperalgesia.[2][3]

- Protocols: In research and investigational settings, ULDN is administered at doses as low as 10 ng/kg, often in combination with opioids. In clinical trials (e.g., Oxytrex), ULDN is combined with oxycodone at doses of 0.002 mg/day, showing enhanced analgesia and reduced hyperalgesia without increased adverse events. ULDN is not commercially available as a stand-alone product, and protocols are not standardized for routine clinical use.[3]

- Side effects: Well tolerated in studies | |[2][3]

Patient Selection for Treatment with Naltrexone – Identifying those most likely to have OIH and those at most risk

Most Likely to have OIH – those with clinical features

Patients considered for low-dose or ultra-low-dose naltrexone (LDN/ULDN) in the management of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) should exhibit clinical features of OIH, including features like worsening pain despite opioid dose escalation, those with reduced pain tolerance., diffuse allodynia, and pain that is not explained by disease progression or new pathology..[1][2][3]

Objective assessment of pain tolerance with the cold pressor test can help identify possible OIH and can also be used to monitor response to therapy.[4] LDN/ULDN is most suitable for patients with refractory pain on chronic opioids, especially those on long term or high-dose regimens.[2]

Those Most at Risk to have OIH

Patients on long term or high-dose regimens (oral morphine equivalent (ME) >850 mg/day) are at greatest risk of OIH. Therapeutic options should be guided by patient risk factors, opioid potency, and response to prior therapy. Patients at high risk include those with escalating doses and repeated dose increases and those with long term opioid use coupled with ineffective benefits for pain and those on high-potency opioids.

Additional risk factors for OIH include those with underlying behavioral health disorders (such as depression or substance use) but more research is needed to clarify which patient populations are most vulnerable.

Opioids relative potency for contributing to OIH – Preclinical (Laboratory and animal studies)

The question arises as to which opioids may pose greater risk for contributing to OIH. Laboratory studies indicate that among commonly used opioids, fentanyl is the strongest in activating Gs protein-coupled signaling that leads to hyperalgesia, followed by methadone and oxycodone, while morphine is less potent but still capable of inducing Gs coupling, especially in neuropathic pain states.

The relative potency among different opioids for activating Gs protein and inducing tolerance appears strongest for fentanyl > methadone > morphine > hydromorphone (dilaudid) > oxycodone. However this process is present for all common opioids, including hydrocodone, a moderate activator, while tramadol and tapentadol (Nucynta), may have a lower risk of OIH and tolerance. Studies of levorphanol are limited.

Relative Potency for Gs Protein Activation and OIH/Tolerance Risk:

– Fentanyl: is the opioid with the greatest effect in activating Gs protein signaling and is most likely to cause opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH), followed by methadone and morphine.

– Oxycodone: promotes Gs coupling, especially in neuropathic pain states.

– Hydromorphone: Demonstrates strong G-protein activation, similar to morphine and oxycodone, and is a full agonist at MOR. However, it is less likely than fentanyl or methadone to cause rapid receptor downregulation and OIH. Hydromorphone is biased toward G-protein signaling over β-arrestin, which may reduce adverse effects and tolerance risk.[1]

– Levorphanol: Acts as a full agonist at MOR, DOR, and KOR, but is G-protein-biased with minimal β-arrestin recruitment. This bias is associated with less respiratory depression and incomplete cross-tolerance with morphine, suggesting a lower risk of OIH and tolerance.[2]

– Hydrocodone: Has moderate efficacy for G-protein activation at MOR, more potent than codeine but less than morphine or hydromorphone. Its risk for OIH and tolerance is considered moderate.[3]

– Tramadol: Is a weak MOR agonist; its active metabolite (desmetramadol) is as effective as morphine in G-protein coupling but spares β-arrestin recruitment, which may reduce OIH and respiratory depression. Tramadol’s overall risk for OIH is low due to its weak MOR activity and dual mechanism.[4][5]

– Tapentadol: Is a moderate MOR agonist, about six times less potent than morphine for G-protein activation, and also inhibits norepinephrine reuptake. Its intrinsic activity at MOR is lower than morphine and oxycodone, and its risk for OIH and tolerance is lower than classic opioids.[6][7]

– Buprenorphine’ is a partial MOR agonist (and kappa and delta antagonist), with low intrinsic efficacy for Gs protein-coupled signaling and is associated with a lower risk of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). Buprenorphine’s partial agonism is also thought to underlie its ceiling effect for respiratory depression and reduced reinforcing effects, as well as its lower tendency for tolerance. Buprenorphine’s kappa antagonism also blocks dynorphin-mediated hyperalgesic signaling which further reduces OIH risk. These features make buprenorphine the preferred opioid for chronic pain management, especially in patients at risk for opioid-related complications.

Summary of Preclinical Data

Hydromorphone and oxycodone are stronger in G-protein activation among the common opioids, but levorphanol’s G-protein bias and tramadol & tapentadol’s weak MOR activity and dual mechanisms confer a lower risk of OIH and tolerance compared to high-potency opioids like fentanyl and methadone. Hydrocodone is intermediate in both potency and risk.

References

-

- Possible Biased Analgesic of Hydromorphone Through the G Protein-Over Β-Arrestin-Mediated Pathway: cAMP, CellKey™, and Receptor Internalization Analyses. Manabe S, Miyano K, Fujii Y, et al. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2019;140(2):171-177. doi:10.1016/j.jphs.2019.06.005.

- Pharmacological Characterization of Levorphanol, a G-Protein Biased Opioid Analgesic. Le Rouzic V, Narayan A, Hunkle A, et al. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2019;128(2):365-373. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000003360.

- Activation of G-Proteins by Morphine and Codeine Congeners: Insights to the Relevance of O- And N-Demethylated Metabolites at Mu- And Delta-Opioid Receptors. Thompson CM, Wojno H, Greiner E, et al. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;308(2):547-54. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.058602.

- Desmetramadol Is Identified as a G-Protein Biased Μ Opioid Receptor Agonist. Zebala JA, Schuler AD, Kahn SJ, Maeda DY. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2019;10:1680. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01680.

- Adult Cancer Pain. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Updated 2025-05-21.

- Μ-Opioid Receptor Activation and Noradrenaline Transport Inhibition by Tapentadol in Rat Single Locus Coeruleus Neurons. Sadeghi M, Tzschentke TM, Christie MJ. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;172(2):460-8. doi:10.1111/bph.12566.

- Tapentadol: A Review of Experimental Pharmacology Studies, Clinical Trials, and Recent Findings. Alshehri FS. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2023;17:851-861. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S402362.

- Opioid Tolerance in Critical Illness. Martyn JAJ, Mao J, Bittner EA. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(4):365-378. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1800222.

Opioids relative potency for contributing to OIH – Clinical Studies

Current comparative clinical data do not demonstrate clear, consistent differences in opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) or tolerance rates among hydrocodone, hydromorphone, tramadol, tapentadol, and levorphanol in chronic pain populations, despite mechanistic differences in G-protein-coupled receptor signaling.

Most available evidence suggests that all opioids can induce tolerance and OIH with long-term use. However, certain patterns have emerged: fentanyl, methadone, morphine, and hydromorphone are most frequently implicated in clinical and case reports, while tramadol and tapentadol are less commonly associated, and levorphanol is rarely reported, likely due to less frequent use and pharmacologic profile.

Tapentadol stands out for better tolerability and lower withdrawal rates in chronic pain RCTs, which may reflect its lower MOR efficacy and additional noradrenergic mechanism, but direct evidence for reduced OIH or tolerance is lacking. A network meta-analysis of RCTs found tapentadol had the lowest incidence of adverse events and trial withdrawal, but did not specifically measure OIH or tolerance as outcomes.

Oxycodone is commonly implicated by clinicians, but not as frequently in published case reports.

Hydromorphone, hydrocodone, and tramadol show no clear advantage over each other in terms of patient satisfaction or withdrawal rates, and levorphanol was rarely included in comparative studies, limiting conclusions about its clinical OIH/tolerance profile.[1]

Mechanistic and pharmacologic studies indicate that all these opioids, when used chronically, can induce receptor desensitization, downregulation, and upregulation of pro-nociceptive pathways, leading to tolerance and OIH. The rate and extent of these adaptations may vary by drug, but clinical studies have not established a hierarchy of OIH risk among these drugs in real-world chronic pain management.[2][3]

Tramadol and tapentadol, due to their weaker MOR agonism and additional monoaminergic actions, likely have a lower risk of OIH, but this is not definitively proven in head-to-head clinical trials.[4][5]

Regarding duration of opioid use, OIH is more likely with prolonged opioid therapy, but the literature does not provide a clear threshold (e.g., weeks, months, or years) at which risk becomes significant.

Regarding higher opioid doses, there is no universally accepted lower cutoff for dosing that ensures safety.

Guidelines and systematic reviews emphasize that differences in analgesic efficacy and adverse event rates among these opioids are small, and no agent offers a clear clinical advantage in preventing OIH or tolerance.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology and CDC guidelines both note a lack of evidence for meaningful differences in long-term outcomes, including OIH, across commonly used opioids for chronic pain.[4][6]

In summary: While mechanistic differences in G-protein signaling exist, current clinical data do not support a significant difference in OIH or tolerance rates among hydrocodone, hydromorphone, tramadol, tapentadol, and levorphanol in chronic pain populations. Tapentadol may be better tolerated, but all opioids require monitoring for tolerance and OIH with long-term use.

References

-

- Tolerability of Opioid Analgesia for Chronic Pain: A Network Meta-Analysis. Meng Z, Yu J, Acuff M, et al. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):1995. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02209-x.

- Opioid Tolerance in Critical Illness. Martyn JAJ, Mao J, Bittner EA. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(4):365-378. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1800222.

- Opioid-Induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia. Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Santoni A. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(10):943-955. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00660-0.

- Use of Opioids for Adults With Pain From Cancer or Cancer Treatment: ASCO Guideline. Paice JA, Bohlke K, Barton D, et al. Journal of Clinical Oncology : Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2023;41(4):914-930. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02198.

- Comprehensive Molecular Pharmacology Screening Reveals Potential New Receptor Interactions for Clinically Relevant Opioids. Olson KM, Duron DI, Womer D, Fell R, Streicher JM. PloS One. 2019;14(6):e0217371. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217371.

- CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain – United States, 2022. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1.

Stratagies for Treatment of OIH

Consider opioid rotation, dose reduction, and early introduction of non-opioid adjuncts.

Cautions and Contraindications

Caution with current opioid dependence or ongoing opioid use due to the risk of precipitated withdrawal.[5] Severe hepatic impairment is a contraindication. The CDC guideline recommends a minimum of 7–10 days opioid-free before starting naltrexone to avoid severe withdrawal.[5] Caution is advised in patients with psychiatric instability, as naltrexone may exacerbate symptoms or complicate management.[5]

Integration Strategies

Protocols for integrating LDN (1–4.5 mg/day) or ULDN (0.125–0.250 mg/day or 10 ng/kg) into opioid tapering may include gradual opioid dose reduction while initiating LDN/ULDN to restore endogenous opioid tone and reduce withdrawal and hyperalgesia.[4][6][7]

Evidence supports improved pain tolerance and reduced withdrawal symptoms when LDN/ULDN is used adjunctively during tapering.[4][6][7] For example, a randomized trial found that very low-dose naltrexone added to methadone taper attenuated withdrawal and craving without increasing adverse events.[6]

Monitoring:

Pain tolerance (e.g., cold pressor test) and clinical pain scores are used to assess response. LDN and ULDN are generally well tolerated, with mild side effects such as vivid dreams or headache.

In summary:

LDN and ULDN are promising adjuncts for OIH, with LDN supported by clinical case series and ULDN by preclinical and early clinical data. LDN is typically dosed at 1–4.5 mg/day orally, while ULDN is used in nanogram doses with opioids (in research settings). More high-quality RCTs are needed to establish standardized protocols and long-term efficacy.

Peripheral Neuropathy

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) shows some evidence of efficacy in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and small fiber neuropathies associated with fibromyalgia, but evidence for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and other small fiber neuropathies is limited and largely anecdotal.

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy:

A single randomized controlled trial found that LDN was as effective as amitriptyline for painful diabetic neuropathy, with a superior safety profile. In this study, LDN significantly reduced pain by 44% in neuropathic conditions, supporting its potential as an alternative or adjunct to standard therapies in diabetic neuropathy.[1][2] However, this evidence is based on a single RCT and retrospective data, so the strength of recommendation is moderate (SOR B).

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy:

There is currently no high-quality randomized controlled trial evidence for LDN in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Most available data are from case series or broader reviews of chronic pain, which mention therapy-related neuropathy as a subset but do not provide robust, condition-specific efficacy data.[3][2] Thus, the evidence for LDN in this indication is weak and primarily anecdotal.

Small Fiber Neuropathy (including Fibromyalgia-associated):

For small fiber neuropathy associated with fibromyalgia, LDN has been studied more extensively. Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses show that LDN is superior to placebo for pain reduction in fibromyalgia, with effect sizes in the small-to-moderate range.[4][5][6] LDN also appears to improve quality of life and other symptoms in some patients, though not all studies reach statistical significance, and the overall strength of evidence is moderate. The mechanism is thought to involve modulation of neuroinflammation and glial cell activity.[7][8][9] However, the most recent large RCT did not find a statistically significant difference in pain reduction compared to placebo, though some secondary outcomes (such as memory) may improve.[6].

Other Small Fiber Neuropathies:

There is insufficient direct evidence for LDN in other small fiber neuropathies not associated with fibromyalgia or diabetes.

Endogenous Opioid Tone

Endogenous opioid tone refers to the baseline activity and availability of the body’s own opioid system—primarily the endogenous opioid peptides (such as endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins) and their receptors—which modulate pain, stress, and mood by providing natural antinociceptive (pain-inhibiting) effects.

In patients with chronic pain treated with long-term opioid therapy, modifying endogenous opioid tone is central to the development and management of opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). Chronic exposure to exogenous opioids leads to adaptive changes: down-regulation and desensitization of opioid receptors, reduced endogenous opioid production, and upregulation of pro-nociceptive pathways (e.g., NMDA receptor activation, increased cAMP signaling, and neuroinflammation). This results in a net decrease in endogenous opioid tone, shifting the balance toward increased pain sensitivity and reduced analgesic efficacy—hallmarks of OIH.[1][2][3][4]

Restoring or enhancing endogenous opioid tone—either by reducing exogenous opioid exposure, using opioid antagonists like low-dose naltrexone, or targeting neuroinflammatory pathways—can help rebalance antinociceptive and pronociceptive signaling, thereby mitigating OIH and improving pain control.[2][3][1] For example, low-dose naltrexone transiently blocks opioid receptors, which can upregulate endogenous opioid production and receptor sensitivity, counteracting the maladaptive changes seen in OIH.

In summary, endogenous opioid tone is the body’s natural pain-inhibiting system. Long-term opioid therapy disrupts this balance, promoting OIH. Interventions that restore endogenous opioid tone can help reverse OIH and improve pain outcomes in chronic pain patients.

References

- Opioid Tolerance in Critical Illness. Martyn JAJ, Mao J, Bittner EA. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(4):365-378. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1800222.

- A Comprehensive Review of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. Pain Physician. 2011 Mar-Apr;14(2):145-61.

- Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Roeckel LA, Le Coz GM, Gavériaux-Ruff C, Simonin F. Neuroscience. 2016;338:160-182. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.029.

- Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Ballantyne JC, Mao J. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(20):1943-53. doi:10.1056/NEJMra025411.

How Naltrexone Works for Pain in Fibromyalgia

Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a key role in the immune system by responding to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that are expressed on infectious agents such as bacteria and viruses. In particular, the TLR-4 receptors stimulate the production of proteins (cytokines) including the inflammatory modulators TNF-α and interleukin-1 that are key players in immune response.

modulates microglial activation via Toll-like receptor 4, resulting in anti-inflammatory effects and reduction of central sensitization

The stimulation of these TLR-4 receptors is believed to contribute to neuropathic pain and the expression of central sensitivity, hyperalgesia (hypersensitivity to painful stimuli), and allodynia (the perception of pain as the result of a non-painful stimulus). These conditions are associated with painful diagnoses including fibromyalgia, migraine headaches, chronic low back pain, TMJ syndrome, interstitial cystitis and endometriosis. TLR-4 receptors are also believed to be involved in opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) and withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia (WIH).

Opioids

Opioids are well known to be effective for pain of all types, though somewhat less so for neuropathic pain. Their effectiveness for pain is based on their activity of stimulating opioid receptors, most importantly the mu-opioid receptor (See Opioids). However, opioids also activate specific TLRs such as TLR-4 which leads to the release of inflammatory modulators including TNF-α and interleukin-1. Constant low-level release of these modulators is thought to reduce the effectiveness of opioids for pain with time and to be involved in both the development of opioid analgesic tolerancs and in the emergence of opioid-induced hypersensitivity to pain.

Morphine‐3‐glucuronide (M3G), a liver metabolite (breakdown product) of morphine, increases neuronal excitability via Toll‐like receptors (TLR). Morphine activation of TLR4, concentrated in spinal glial cells causes the release of inflammatory proteins (interleukin‐1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF‐α), that result in neuroinflammation and increased pain. It is believed that M3G is a significant contributor to the side effects of morphine and that individual variants, genetic-based or otherwise, lead to greater M3G levels in some patients causing greater intolerance of morphine. This can be especially true in patients with compromised renal function which leads to reduced elimination of M3G and greater symptoms of toxicity.

Opioid Antagonists and Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

Opioid antagonists that have the opposite effect of opioids by blocking the activity of opioids are now being explored for new applications in pain management. Certain opioid antagonists (actually reverse agonists), including naloxone and naltrexone, not only function to block opioid activity at opioid receptors but they also block or antagonize activity at the TLR-4 receptors as well. This is believed to reduce the neuroinflammation triggered by TLR-4 and may be of benefit in the treatment of the neuropathic pain conditions described above. In fact, there is a growing body of research suggesting that low dose naltrexone may be effective for fibromyalgia and other conditions associated with central sensitivity.

Due to their antagonizing activity with opioids, ordinarily they cannot be given simultaneously with opioids unless at low doses (<10 mg). However, research has shown that naloxone and naltrexone both exists as enatiomers, or both left- and right-handed versions that are molecular mirror images of one another much like a left or right handed glove. While typically medications are manufactured as combinations of both left- and right enatiomers in equal distributions, it is possible to isolate the left- from the right enatiomer. Chemically identical but structurally different, the right (dextro) version of naltrexone antagonizes activity of TLR-4 but has no affinity for, and does not affect, opioid receptors. Thus, the dextro-enantiomer of naltrexone may be effective in treating pain by blocking TLR-4 while not affecting the opioid receptors, thereby avoiding adverse effects associated with blocking the opioid receptors. This discovery represents a potentially useful breakthrough in the management of neuropathic pain and related syndromes.

Other Microglial Inhibitors

Some research suggests that minocycline, an antibiotic, may inhibit microglial activity by mechanisms unrelated to antibiotic activity, possibly at the TLR-4 receptor. Animal studies have shown that minocycline inhibits heat-related hyperalgesia.

Resources:

Reference Articles:

References for Efficacy and Protocols

- The Effects of Low Dose Naltrexone on Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia and Fibromyalgia. Jackson D, Singh S, Zhang-James Y, Faraone S, Johnson B. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:593842. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.593842.

- Antinociceptive Effect of Ultra-Low Dose Naltrexone in a Pre-Clinical Model of Postoperative Orofacial Pain. Hummig W, Baggio DF, Lopes RV, et al. Brain Research. 2023;1798:148154. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2022.148154.

- Oxycodone Plus Ultra-Low-Dose Naltrexone Attenuates Neuropathic Pain and Associated Mu-Opioid Receptor-Gs Coupling. Largent-Milnes TM, Guo W, Wang HY, Burns LH, Vanderah TW. The Journal of Pain. 2008;9(8):700-13. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.005.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone’s Utility for Non-Cancer Centralized Pain Conditions: A Scoping Review. Rupp A, Young E, Chadwick AL. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2023;24(11):1270-1281. doi:10.1093/pm/pnad074.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain: Update and Systemic Review. Kim PS, Fishman MA. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2020;24(10):64. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00898-0.

- Low Dose Naltrexone in the Management of Chronic Pain Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Hegde NC, Mishra A, V D, et al. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2025;29(1):96. doi:10.1007/s11916-025-01411-1.

- The Use of Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN) as a Novel Anti-Inflammatory Treatment for Chronic Pain. Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D. Clinical Rheumatology. 2014;33(4):451-9. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2517-2.

- The Utilization of Low Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain. Poliwoda S, Noss B, Truong GTD, et al. CNS Drugs. 2023;37(8):663-670. doi:10.1007/s40263-023-01018-3.

References for Patient Selection and Integration Strategies

- A Comprehensive Review of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. Pain Physician. 2011 Mar-Apr;14(2):145-61.

- Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia in Patients With Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review of Published Cases. Guichard L, Hirve A, Demiri M, Martinez V. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2021;38(1):49-57. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000994.

- Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia: Clinical Implications for the Pain Practitioner. Silverman SM. Pain Physician. 2009 May-Jun;12(3):679-84.

- The Effects of Low Dose Naltrexone on Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia and Fibromyalgia. Jackson D, Singh S, Zhang-James Y, Faraone S, Johnson B. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:593842. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.593842.

- CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain – United States, 2022. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1.

- Very Low Dose Naltrexone Addition in Opioid Detoxification: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Mannelli P, Patkar AA, Peindl K, et al. Addiction Biology. 2009;14(2):204-13. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00119.x.

- Oxycodone Plus Ultra-Low-Dose Naltrexone Attenuates Neuropathic Pain and Associated Mu-Opioid Receptor-Gs Coupling. Largent-Milnes TM, Guo W, Wang HY, Burns LH, Vanderah TW. The Journal of Pain. 2008;9(8):700-13. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.005.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone’s Utility for Non-Cancer Centralized Pain Conditions: A Scoping Review. Rupp A, Young E, Chadwick AL. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2023;24(11):1270-1281. doi:10.1093/pm/pnad074.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain: Update and Systemic Review. Kim PS, Fishman MA. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2020;24(10):64. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00898-0.

Naltrexone for Pain – Low Dose Naltrexone

-

- The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain. 2014

- Association of low-dose naltrexone and transcranial direct current stimulation in fibromyalgia- – 2022

- Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN) for Chronic Pain at a Single Institution- A Case Series – 2023

- Low-dose naltrexone’s utility for non-cancer centralized pain conditions- a scoping review – 2023

- Low-dose naltrexone for treatment of pain in patients with fibromyalgia- a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study – 2023

- The Safety and Efficacy of Low-Dose Naltrexone in Patients with Fibromyalgia- A Systematic Review – 2023

- Efficacy of Low-Dose Naltrexone and Predictors of Treatment Success or Discontinuation in Fibromyalgia and Other Chronic Pain Conditions – 2023

- A systematic literature review on the clinical efficacy of low dose naltrexone and its effect on putative pathophysiological mechanisms among patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia – 2023

- Opiate Antagonists for Chronic Pain- A Review on the Benefits of Low-Dose Naltrexone in Arthritis versus Non-Arthritic Diseases – 2023

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Use for Patients with Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome- A Systematic Literature Review – 2021

- Depression in Fibromyalgia Patients May Require Low-Dose Naltrexone to Respond- A Case Report – 2022

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Co-Treatment in the Prevention of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia – 2021

- Sjogren’s Syndrome and Clinical Benefits of Low-Dose Naltrexone Therapy_ Additional Case Reports – PubMed – 2020

- Effective Doses of Low-Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain – An Observational Study – 2024

- Adding Ultralow-Dose Naltrexone to Oxycodone Enhances and Prolongs Analgesia- A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Oxytrex – 2005

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Usage in Multiple Sclerosis _ National MS Society

- Potential Therapeutic Benefit of Low Dose Naltrexone in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis_Chronic Fatigue Syndrome_ Role of Transient Receptor Potential – PubMed- 2021

- The Effects of Low Dose Naltrexone on Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia and Fibromyalgia – 2021

- Cohort study based on data from the Norwegian prescription database – PubMed – 2017

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Co-Treatment in the Prevention of Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia – 2021

- Low-dose naltrexone and opioid consumption_ a drug utilization cohort study based on data from the Norwegian prescription database – PubMed – 2017

- Low Dose Naltrexone In The Management Of Chronic Pain Syndrome_ A Meta-Analysis Of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials – PubMed – 2025

- Is low-dose naltrexone effective in chronic pain management? – YES. – 2023

- Therapeutic Uses and Efficacy of Low-Dose Naltrexone- A Scoping Review – 2025

- Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN) for Chronic Pain at a Single Institution- A Case Series – 2023

- Low-dose naltrexone, an opioid-receptor antagonist, is a broad-spectrum analgesic_ a retrospective cohort study – PubMed – 2022

- Effective Doses of Low-Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain – An Observational Study – 2024

References for Peripheral Neuropathy Section

- Is Low-Dose Naltrexone Effective in Chronic Pain Management?. Radi R, Huang H, Rivera J, Lyon C, DeSanto K. The Journal of Family Practice. 2023;72(7):320-321. doi:10.12788/jfp.0654.

- The Utilization of Low Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain. Poliwoda S, Noss B, Truong GTD, et al. CNS Drugs. 2023;37(8):663-670. doi:10.1007/s40263-023-01018-3.

- Low Dose Naltrexone for Refractory Cancer Pain: Case Series of Initial Safety and Effectiveness. Malik A, Ye A, Chung M. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2025;:S0885-3924(25)00798-5. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2025.08.015.

- Low Dose Naltrexone in the Management of Chronic Pain Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Hegde NC, Mishra A, V D, et al. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2025;29(1):96. doi:10.1007/s11916-025-01411-1.

- A Systematic Literature Review on the Clinical Efficacy of Low Dose Naltrexone and Its Effect on Putative Pathophysiological Mechanisms Among Patients Diagnosed With Fibromyalgia. Partridge S, Quadt L, Bolton M, et al. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15638. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15638.

- Naltrexone 6 Mg Once Daily Versus Placebo in Women With Fibromyalgia: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Due Bruun K, Christensen R, Amris K, et al. The Lancet. Rheumatology. 2024;6(1):e31-e39. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00278-3.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone for Chronic Pain: Update and Systemic Review. Kim PS, Fishman MA. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2020;24(10):64. doi:10.1007/s11916-020-00898-0.

- The Use of Low-Dose Naltrexone (LDN) as a Novel Anti-Inflammatory Treatment for Chronic Pain. Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D. Clinical Rheumatology. 2014;33(4):451-9. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2517-2.

- Low-Dose Naltrexone’s Utility for Non-Cancer Centralized Pain Conditions: A Scoping Review. Rupp A, Young E, Chadwick AL. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2023;24(11):1270-1281. doi:10.1093/pm/pnad074.

- The Safety and Efficacy of Low-Dose Naltrexone in the Management of Chronic Pain and Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis, Fibromyalgia, Crohn’s Disease, and Other Chronic Pain Disorders. Patten DK, Schultz BG, Berlau DJ. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(3):382-389. doi:10.1002/phar.2086.

Naltrexone for Pain – Overviews

Naltrexone – Opioid Tolerance and Dependence

- Ultra-low-dose opioid antagonists enhance opioid analgesia while reducing tolerance, dependence and addictive properties

- Ultra Low Dose Naltrexone – For Lower Opiate Tolerance – Research Summary

Naltrexone – Fibromyalgia

- Effects of Naltrexone on Pain Sensitivity and Mood in Fibromyalgia – 2009

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Eases Pain and Fatigue of Fibromyalgia

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Effective Therapy for Fibromyalgia

- Naltrexone for Fibromyalgia – Learn About Research Studies!

- fibromyalgia-symptoms-are-reduced-by-low-dose-naltrexone-a-pilot-study-2009

- Low-dose naltrexone for the treatment of fibromyalgia: findings of a small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, counterbalanced, crossove – 2013 – PubMed – NCBI

- The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain – 2014

- Reduced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines after Eight Weeks of Low-Dose Naltrexone for Fibromyalgia – 2017

- Combine Opiate and Opiate Blocker for Less Fibromyalgia Pain? — Dr Ginevra Liptan

- Three Letters You Need to Know If You Have Fibromyalgia: LDN — Dr Ginevra Liptan

- Answers to Some FAQs on Low-Dose Naltrexone — Dr Ginevra Liptan

- Lessons Learned on Opiates and LDN for Fibromyalgia — Dr Ginevra Liptan

- Low-dose naltrexone for the treatment of fibromyalgia: findings of a small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, counterbalanced, crossover – 2013 – PubMed – NCBI

- Aversive effects of naltrexone in subjects not dependent on opiates. – PubMed – NCBI

- Reduced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines after Eight Weeks of Low-Dose Naltrexone for Fibromyalgia – 2017

- Low Dose Naltrexone in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. – PubMed – NCBI 2018

- Efficacy of Low-Dose Naltrexone and Predictors of Treatment Success or Discontinuation in Fibromyalgia and Other Chronic Pain Conditions- A Fourteen-Year, Enterprise-Wide Retrospective Analysis – 2023

Naltrexone – Ultra Low Dose Naltrexone

- Ultra Low Dose Naltrexone – For Lower Opiate Tolerance – Research Summary

- Ultra-low-dose naltrexone suppresses rewarding effects of opiates and aversive effects of opiate withdrawal in rats. – PubMed – NCBI

- Ultra-low-dose opioid antagonists enhance opioid analgesia while reducing tolerance, dependence and addictive properties

- Ultra-low dose naltrexone attenuates chronic morphine-induced gliosis in rats – 2010

- Ultra-Low Doses of Naltrexone Enhance the Antiallodynic Effect of Pregabalin or Gabapentin in Neuropathic Rats. – PubMed – NCBI

- Ultra-Low-Dose Naloxone or Naltrexone to Improve Opioid Analgesia – The History, the Mystery and a Novel Approach – 2010

- Adding Ultralow-Dose Naltrexone to Oxycodone Enhances and Prolongs Analgesia- A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Oxytrex – 2005

- The Endocannabinoid System Contributes to Electroacupuncture Analgesia – 2021

Naltrexone – Arthritis

Naltrexone – Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Chrohns & Ulcerative Colitis)

- Therapy with the Opioid Antagonist Naltrexone Promotes Mucosal Healing in Active Crohn’s Disease – A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial – 2011

- Low dose naltrexone for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease (Cochrane Review)-2018

- Low-Dose Naltrexone Therapy Improves Active Crohn’s Disease – 2007

Naltrexone – Interstitial Cystitis & Systemic Inflammation

- Inflammation and Inflammatory Control in Interstitial Cystitis: Bladder Pain Syndrome – Associations with Painful Symptoms – 2014

- Inflammation and Symptom Change in Interstitial Cystitis: Bladder Pain Syndrome – A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network Study – 2016

- Toll-like Receptor 4 and Comorbid Pain in Interstitial Cystitis: Bladder Pain Syndrome – A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network Study – 2015

- Inflammation and central pain sensitization in Interstitial Cystitis:Bladder Pain Syndrome – 2015

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.