“It takes but one positive thought when given a chance to survive and thrive to overpower an entire army of negative thoughts.”

– Robert H. Schuller

Neck Pain

Although less common than low back pain, neck pain affects 10% of the population of the United States. The anatomic source of neck pain may be myofascial (muscle), ligaments, bone, intervertebral discs, nerve, skin, or viscera (organs), including the heart. Possible causes include damage of tissue due to trauma, compression of nerves, inflammation, malignancy, infection, or degenerative (“wear and tear”) processes.

See Also:

Neck Pain – Overview

Neck – Disc Pain

Neck – Facet Pain

Neck – Myofascial Pain

Neck – Radiating Pain

Neck – Shoulder Pain

Neck – Spinal Stenosis

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

Neck – Surgery:

.

Neck Pain

Neck pain may originate from pathology within the neck (primary) or neck pain may be referred from other parts of the body (secondary). The focus of this section is on primary neck pain. In primary neck pain, pain can arise from the supportive structures of the cervical skeleton including muscles and their ligament attachments, the facet (or zygapophyseal) joints, the fibrous capsule (annulus fibrosus) of the intervertebral discs or from nerve structures. The nerve structures most commonly involved are the spinal nerve roots exiting the spinal cord bilaterally at each cervical vertebral level, but predominantly the lower neck, nerves C-4 through C-8.

The spinal cord itself is insensitive to pain but the membranes covering the cord, the arachnoid and dura, have nerve endings and registers pain. When the spinal cord in the neck is compressed by a herniated disc, enlarged facet joint and/or bone spur, complaints may include lack of coordination, clumsiness in gait or use of the upper extremities, and alterations in bowel and bladder control (incontinence or retention).

Neck Pain Based on Anatomic Source

Neck Pain: Myofascial

When evaluating neck pain based on anatomic source, the most common source is myofascial, pain arising from muscle and fascia, the tough membrane surrounding muscle and other tissues in the body. Muscle pain develops as a result of trauma, either abruptly such as in a whiplash injury or gradually, associated with other spinal injury when muscles tighten up to reduce movement of injured tissues, as may occur with a ruptured disc or chronic facet arthritis.

A very underappreciated atraumatic cause of myofascial pain in the neck and shoulders is that which evolves slowly as a result of prolonged muscle tension related to stress. When muscles remain in prolonged contraction, perceived as being tense or tight, muscle fibers develop painful areas called trigger points (RrP). As TrPs evolve over time they begin as points of muscle tenderness noted only upon palpation or stretching of the muscle, developing into a source of spontaneous pain, requiring neither palpation nor stretching. TrPs further evolve into sources of referred pain in which the pain is perceived in patterns distributed beyond the source location.

TrPs are most commonly found in the neck and shoulders with referral patterns responsible for headaches, facial pain and pain extending down the arms or into the uppar back and shoulders. Myofascial and TrP pain can be constant or intermittent and can be quite severe, to the point of requiring opioids for relief. In fact, TrPs and their referral patterns can mimic the pain associated with herniated discs and facet pain, leading to aggressive treatment modalities including surgery and interventional procedures, including epidural steroid injections and nerve blocks to obtain relief. Unfortunately, neither surgery nor these interventional procedures will be effective for TrP pain and can actually make TrP pain worse.

For more information regading myofascial pain, trigger points and their treatment:

See Myofascial Pain

Neck Pain: Neurogenic (Nerve Root)

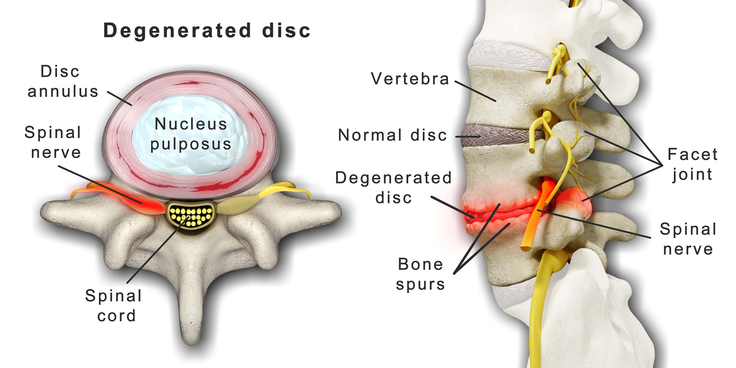

Neck pain generated from spinal nerve roots is a result of compression or chemical irritation. Compression of a nerve root can occur with disc bulging or herniation, enlargement of facet joints adjacent to the nerve root, bone spurs or a combination of any or all three. Chemical irritation of nerve roots can occur when discs are injured and leak contents that are inflammatory, especially when herniated discs extrude highly irritating components of the nucleus pulposis, or central core of the disc. Bone spurs can result from trauma or degenerative processes related to chronic use and repetitive overuse.

Neurogenic pain from affected nerve roots is typically described as burning, electric, tingling and sometimes sharp or stabbing. The location and distribution of nerve root pain varies based on the nerve root involved in patterns called dermatomes. A dermatome is “an area of the skin supplied by nerves from a single spinal root” Dermatomes have been carefully mapped to demonstrate “typical” anatomic distributions but, unfortunately, there is a great deal of individual variation that render these maps unreliable.

Disc protrusions and herniations are common sources of nerve root compression and irritation. A posterior lateral disc protrusion results in compression of the nerve whose number corresponds to that of the lower vertebral body. For instance, a disc protrusion at the C5-6 interspace involves the 6th nerve root. The most common location for a disc protrusion is C5-6, followed closely by C6-7, and then by C4-5. Protrusions at C2-3 and C7-T1 can occur but are rare.

Spinal nerve roots exit the spinal cord through windows (neural foramen) at each level of the cervical spine. In the normal cervical spine, the cervical nerve root occupies about one third of the neural foramen. Degenerative changes of the spine, hypertrophy (enlargement) of ligaments, and intervertebral disc protrusions decrease the available space of the nerve. When the patient extends his/her neck, the neural foramen decrease

s in size, which accentuates nerve root compression. If neck extension is not painful, it is unlikely that the pain is caused by nerve root compression in the neural foramen.

Radicular Pain

Compression or irritation of the C-6 nerve root typically results in a “radicular” pattern of pain, extending down the arm and to the hand, thumb and index finger. With the C-7 nerve root the radicular pattern of pain typically extends down the arm and to the hand and middle finger while similarlly the C-8 nerve root involves the 5th finger. Although disc protrusions at C3-4 are not common, when they occur and the fourth nerve root is compressed, the pain distribution is to the superior aspect of the shoulder rather than into the arm, forearm, or hand.

Neck Pain: Facet

The facet joints in the neck providing movement forward (flexion), backward (extension), leaning side to side (abduction) and rotation can be sources of pain, typically as a result of arthritis or trauma.

Neck Pain: Discs

Pain arising from damaged discs can arise from the disc itself or from nerve roots that are either compressed by the disc or irritated by inflammatory chemicals released from the damaged disc. The fibrous capsule (annulus) of intervertebral discs contains pain receptors that register pain when discs are damaged or disrupted (discogenic pain). Discogenic pain has pain referral patterns that are typical for each cervical disc. While individual variations are common, knowing usual pain referral patterns can help correlate findings on MRIs with a person’s percieved pain to accurately define a source. Referral patterns from disrupted discs can be unilateral or bilateral.

The following discogenic pain referral patterns have been identified:

The C3-C4 disc refers pain to the neck, subocciput, trapezius, anterior neck, face, shoulder, interscapular and limb.

The C4-C5 disc refers pain to the neck, shoulder, interscapular, trapezius, extremity, face, chest and subocciput.

The C5-C6 disc refers pain to the neck, trapezius, interscapular, suboccipital, anterior neck, chest and face.

The C6-C7 disc refers pain to the neck, interscapular, trapezius, shoulder, extremity and subocciput.

The C7-T1 disc refers pain to the neck and interscapular area.

Physical Exam

Findings on exam may identify features that allow identification of the specific spinal nerves responsible for pain and other symptoms arising ftom their compression or irritation. Certain findings can suggest specific abnormalities.

Identifying Cervical Vertebra on Exam of the Neck

It is often thought that the most prominent protruding spinous process at the base of the neck is the 7th cervical vertebra, but the C-6 vertabra is actually more prominent than C-7 in 30-40% of the population, making simple palpation inaccurate. Because the C-7 vertebra does not move freely due to it’s attachment to T-1, the uppermost thoracic vertebra. the C-6 vertebra is the lowest freely moving cervical vertebra. Therefore, by palpating the most prominent lowest cervical vertebra while flexing and extending the neck, if the vertebra moves it is C-6, if not it is C-7. This flexion-extension technique is accurate 77.1% of the time.

Arm-Abduction Sign

The arm-abduction sign, when pain is relieved by resting hand on head, is usually positive in cervical nerve root compression. Theoretically, tension on the nerve is decreased by arm abduction. This may be the only position of comfort for patients with large lateral disc herniations.

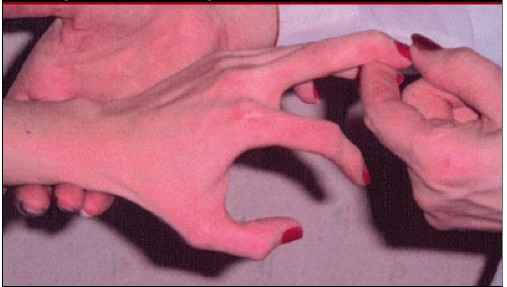

Hoffmann’s sign

Hof fmann sign is used to predict cervical spinal cord compression. Hoffmann’s sign, elicited by flicking the distal phalanx of the long finger. A negative response is no motion of the thumb. A positive response is flexion of the thumb at the interphalangeal joint. The sensitivity of the Hoffmann sign relative to cord compression was 58%, specificity 78%, positive predictive value 62%, negative predictive value 75%.

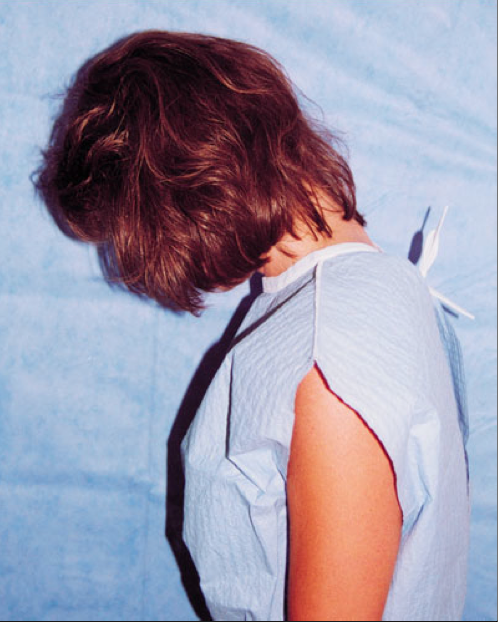

Lhermitte’s sign

Lhermitte’s sign is performed by asking the patient to maximally flex her neck. The test is positive if this causes shooting, electric-like pain down the spine, often into the legs, arms, and sometimes to the trunk. Lhermitte’s sign is caused by miscommunication between the nerves that have become demyelinated, a condition in which the normal insulating outer layer of the nerve is lost. Conditions associated with a positive Lhermitte’s sign include neck trauma, prolapsed cervical disc, multiple sclerosis

and radiation myel

itis.

Sensation

A decreased pin-prick sensation in the distribution of a cervical nerve root along with neck pain strongly suggests a compression of the cervical nerve root. The cervical nerves all have a sensory component; however, only nerve roots of C5-T1 have identifiable motor (muscle) components. When the nerves above C5 are involved, the pattern of sensory deficit is the only positive physical finding that allows localization.

Strength

Different muscles are innervated by specific spinal nerves and the presence of weakness allows identification of an affected nerve. The amount of weakness indicates the degree of damage to the motor component of the nerve. In nerve root compression, it is not uncommon to discover weakness that the patient may not be aware of.

Reflexes

In most patients with neck pain, an absent or depressed deep-tendon reflex is the result of nerve root compression. When the reflexes are hyperactive, the lesion is centrally located either in the spinal cord or brain involving the pyramidal system. While the intensity of deep-tendon reflexes is variable between normal individuals; however, asymmetry in reflex response usually indicates pathology.

Sources of Chronic Low Back Pain (LBP)

Chronic low back pain is usually multifactorial. The major anatomic sources include the lumbar intervertebral discs, the facet joints, the sacro-iliac (SI) joints, and the soft tissues: muscles, ligaments and fascia (fibrous tissue surrounding muscles. The intervertebral disc is estimated to be the most common source of chronic LBP, estimated by one authority to represent up to 42%, with the facet joints the next most common source accounting for up to 31% and the SI joint up to 18%. Other authorities consider the soft tissues to be the most common source of LBP as they accompany all the other conditions most of the time.

Age correlates with the source of chronic LBP. Specifically, lumbar intervertebral disc cases were found to be significantly younger (average age 43.7 years) than cases of facet joint pain cases (59.8 years ) and SI pain cases (62.3 years).

The spine consists of bony elements, the vertebrae, that are separated from one another by intervertebral discs that function as shock absorbers to prevent damage from bone-against-bone trauma related to movement of the spine. Along both sides of the spine are facet joints that provide for movement of the spine, including forward “flexion,” backward “extension,” leaning laterally and twisting. Connecting the vertebrae are ligaments, tendons and muscles, along with the fascia, the fibrous tissure surrounding all musculoskeletal components. There are nerve receptors in each of these components capable of sourcing pain, both locally and in referral patterns, causing a spread of pain to other areas.

To successfully identify pain sources, it is important to understand the character and patterns of pain that generally accompany each anatomic source of pain, including their referral patterns. This is not an exact science, as there are overlaps in pain characteristics and referral patterns as well as individual variations in anatomy and pain perceptions from one patient to the next. The treatment of pain therefore may require a trial and error approach until a successful outcome can be achieved.

There are multiple arguments in favor of, or against, the diagnostic accuracy of controlled local anesthetic blocks, but controlled local anesthetic blocks continue to be the best available tool to identify intervertebral discs, facet, or sacroiliac joint(s) as the source of low back pain. Unfortunately, these procedures are invasive, expensive, painful and often difficult to interpret, and therefore they may not be suitable for routine clinical use as a primary diagnostic modality. This leaves clinical assessment as the only process in many cases.

It is also important to understand that a finding on an imaging study such as an MRI that may appear grossly abnormal may nevertheless not be a source of pain. Clinical correlation is essential to determine the importance of abnormalities on imaging studies. Too often patients and clinicians chase these “abnormal” findings with treatments and procedures that are destined to fail from the beginning. A thorough assessment of pain is usually required to direct a successful treatment plan.

Treatment of Chronic Neck Pain

Successful management of chronic neck pain often requires an “integrative” approach, that is a treatment regimen that incorporates a multi-disciplinary collection of treatment options that include education, exercise, trigger point therapy, massage, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, diet and nutritional supplements, medications and mind-body disciplines such as yoga and tai chi. These topics are covered elsewhere on this website.

Procedures:

Facet joint injections and nerve procedures

A Different Paradigm for the Assessment and Management of Neck Pain

The correct identification of an anatomical source of pain is of critical importance to guide surgical or procedural techniques for the successful management of pain. However, in clinical practice the exact sources of pain is often elusive and poorly defined even with careful assessment. Patients often experience this when a physician makes a diagnosis followed by a surgical or interventional procedure that is unsuccessful in reducing pain.

Then a second, or

the same, physician follows with a different diagnosis as to the source of pain and a different recommended treatment. This does not necessarily reflect incompetence but rather the imprecision of the diagnostic process based on a great deal of overlapping manifestions of different anatomic sources of pain as well as individual variation.

Because it has been clearly demonstrated that accuracy of determining an anatomic source of neck pain is often lacking, it can be argued that the management of neck pain may require a “mechanistic” approach rather than an “anatomic” approach. In other words, as physician’s understanding of the mechanisms of pain has grown, it is possible to identify the likely mechanism of a pain even if the specific anatomic source may be uncertain.

Three mechanism-based classifications of pain have been identified:

- Nociceptive

- Peripheral Neuropathic

- Central Sensitization

It has been established that pain states are characterized by a dominance of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms that may be distinguishable from one another clinically, based on the pattern recognition of clusters of symptoms and signs particular to each category. Consequently, management of pain can be guided by understanding the mechanism of the pain even when the source is not clearly identified. It has been established that certain medications, nutriceutical supplements and other treatment interventions have effectiveness based on these mechanisms of pain.

For example, true “sciatica” is nerve pain generated by irritation or compression of one or more lumbar nerve roots. It is likely experienced as “burning” or “electric” with a referral pattern that can be severe and follows a narow band of distribution. By identifying this pain as “peripheral neuropathic” pain and engaging medical management directed specifically at this nerve pain, successful pain control may be achieved without necessitating expensive imaging or procedures.

See: Neurobiology of Pain

References

Neck Pain – Overviews

Neck Pain – Assessment

- Lhermitte’s Sign: The Current Status – 2015

- Cervical Spinal Cord Compression and the Hoffman Sign

- Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain – Does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? – 2009

- On the variations of cervical dermatomes – 2014

- Identification of the Correct Cervical Level by Palpation of Spinous Processes

Neck Pain – Mechanisms of Pain

- The Discriminative Validity of “Nociceptive,” ” Peripheral Neuropathic,” and “Central Sensitization” as Mechanisms-based Classifications of Musculoskeletal Pain – 2011

- Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians – 2010

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.