“The greatest evil is physical pain”

– Saint Augustine

Arachnoiditis

Arachnoiditis is a disease characterized by inflammation of the arachnoid membrane, one of the three membranes that cover and protect the brain, the spinal cord and the nerve roots. The space between the outer membrane, the dura, and the middle membrame, the arachnoid, contains the cerebrospinal fluid which circulates from the brain to the sacral area at the base of the spine. The arachnoid membrane contains blood vessels and immune cells and can become inflamed if irritated or damaged.

Inflammation of the arachnoid can result in scarring and fibrosis which can cause abnormal adhesions and clumping of the nerves at the base of the spinal cord and those exiting the spinal cord. These adhesions and clumping can significantly alter the function of the nerve and the spinal cord that can lead to severe chronic nerve pain, numbness, tingling, weakness in the legs and a variety of neurological impairments.

See below for causes and treatment

See Also:

Low Back Pain (LBP) – Overview

LBP – Superior Cluneal Nerve Entrapment

LBP – Failed Back Surgery Syndrome

LBP – Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

Treatment Procedures:

Facet Joint Injections and Nerve Procedures

LBP – Surgery:

.

Arachnoiditis

Epidemiology

Arachnoiditis is a rare disorder. Unfortunately, the precise prevalence and incidence of arachnoiditis is unknown. According to one estimate, approximately 11,000 new cases occur each year in the USA. The increasing number of neck and back surgeries, pain relief procedures and diagnostic interventions and anesthetic spinal interventions has increased the number of cases considerably. Since some cases of arachnoiditis may go misdiagnosed or undiagnosed, it is difficult to determine its real frequency in the general population.

Arachnoiditis affects more females than males, possibly because two thirds of the pregnant women in the USA receive spinal or epidural anesthesia for their delivery. Current evidence, however, does not confirm that routine, uncomplicated epidural analgesia in obstetrics when using preservative-free, low concentration bupivacaine with opioids or plain bupivacaine, if performed in the standard way with disposable equipment, causes arachnoiditis.

A Quick Review of the Pertinent Anatomy of the Spinal Cord

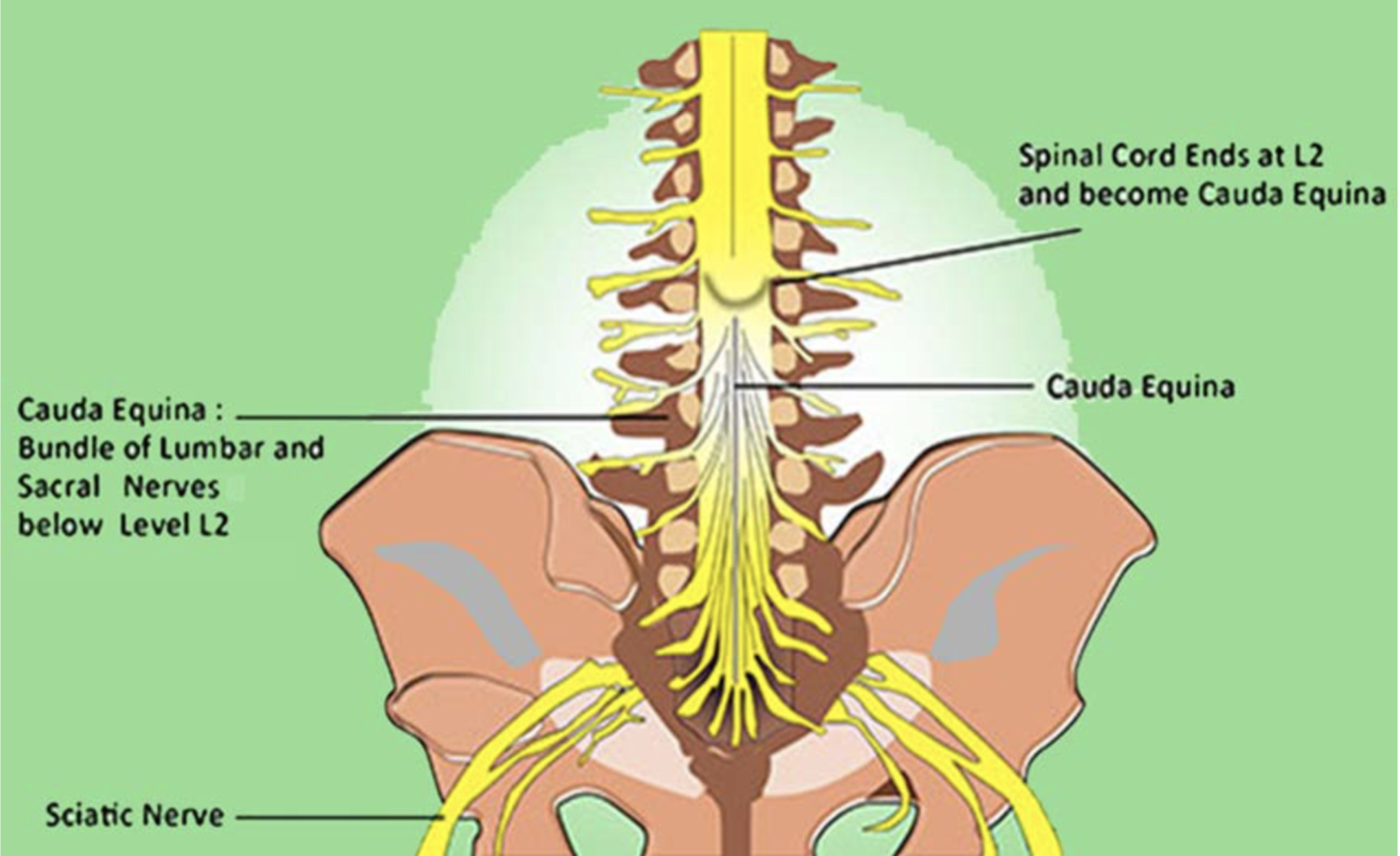

The spinal cord starts at the base of the brain and extends down the vertebral canal to about the first lumbar vertebra of the lower back. The end is cone-shaped and is known as the “conus medullaris.” At the level of the conus medullaris the spinal cord splits up into about 2 dozen nerves known as nerve roots or collectively as the “cauda equina” (in Latin this means “horses tail” due to the visual similarity). The cauda equina extends downward to the sacrum.

These nerve roots are encased in a protective sac known as the thecal sac. Its outer lining is called the dura mater (dura), and the inner-most layer is the arachnoid. Within the thecal sac is the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) which serves to nourish the nerve roots and wash away toxic materials such as elements that may result from inflammation. The small nerve roots are always floating in CSF and protected by the dura. Any contaminant or irritant that enters the thecal sac may initiate an inflammatory process.

Signs & Symptomsa of Arachnoiditis

Most symptoms are initially due to inflammation in the area of damage to the dura and/or the arachnoid membranes. However, arachnoiditis is usually a progressive disorder. First it is characterized by inflammation of the arachnoid membrane and then invasion of the subarachnoid space where the pain remains localized and can be quite severe. Eventually, as the inflammation spreads to the nerve roots after a few months, they begin to adhere to each other causing pressure on the nerve roots which leads to scarring and fibrosis that restricts blood flow to the affected area and also impedes the flow of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). The progression of the localized pain to other areas depends on which nerves are involved. This condition can occur in the neck but is most common in the lower lumbar spine.

When the acute inflammatory process progresses to the chronic condition associated with adhesions, it is referred to as “adhesive arachnoiditis” or AA. In AA, inflamed nerve roots stick or adhere (forming an adhesion) to the arachnoid lining. Early in arachnoiditis the symptoms may come from only one inflamed nerve root but the inflammation may progress to the point that the nerve roots have adhered to the arachnoid lining. As the inflammation worsens and spreads to develop adhesions, it can cause severe pain and dysfunction of the nerves that connect to the stomach, intestine, sexual organs, pelvis, legs, and feet.

Adhesive Arachnoiditis (AA)

Symptom severity of AA depends initially on the extent and location of the initial injury whereas continued chronic severity depends on the extent of spread of inflammation, severity of adhesions and degree of impairment of the CSF circulation. Most AA occurs in the lumbar region with the pain usually felt in the lower back, the perineal area between rectum and genitals, the legs and feet. These symptoms may appear weeks after spinal surgery or interventional procedures such as epidural injections. In most cases the pain is intense, accompanied by tingling or burning in the legs or feet and skin sensations like “bugs crawling” or “water dripping.”

Frequently patients complain of constant severe pain radiating to the lower extremities, muscle cramps and difficulty walking and impaired balance. Also, patients may suffer from symptoms related to “central sensitization,” a condition associated with chronic pain and neuroinflammation. With central sensitization the function of the autonomic nervous system becomes dysregulated leading to disruption of the normal function of the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and urinary systems. This process leads to a wide range of symptoms, including severe headaches, vision disturbances, hearing problems, dizziness and fatigue. Bowel, bladder and sexual dysfunction as well as “electric shocks” type of pain are common in patients with severe adhesive arachnoiditis.

See Central Sensitization and Neuroinflammation

Cardiovascular Symptoms

As related to autonomic dysregulation, patients with AA may develop palpitations, postural lightheadedness or drops in blood pressure. Sympathetic-parasympathetic imbalance may be responsible for frequent sweating and heat intolerance and dysregulation of the peripheral circulation may manifest as uneven or unstable blood flow in the extremities leading to asymmetric discoloration of the skin and alternating warm or cold extremities.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

In a 2017 study evaluating a large population of AA patients, bowel dysfunction consisting mostly of constipation was identified in 64% of the patients but this was usually related to opioid use. Intermittent episodes of diarrhea were found in 26.9% of patients.Nausea and vomiting are not uncommon. Severe constipation requiring either colostomy or frequent removal of fecal impaction was noted in 1.6%. Rectal incontinence was noted in 19.9% of women and 7.7% of men.

Urinary Symptoms

Urinary systmes may include inappropriate frequency of urination as well as difficulty initiating or stopping urination and incomplete emptying of the bladder which in turn may predispose to urinary tract infections. Symptoms may also include dripping or leaking of urine as a result of a dysfunctional sphincter. In more severe cases, patients may experience urinary incontinence or neurogenic bladder. Urinary symptoms are more frequent and more severe in females than in males.

Sexual Dysfunction

In men, impotencei is the most common dysfunction, partial (60%) or total (40%). In the same study above, only 2.3 % of women denied sexual dysfunction, while 83.2 % of women reported loss of libido and 46% complained of pain with penetration. Lower back pain during intercourse was noted by 84.6% of women and 13.2% also had pain in their lower extremities. Regarding sexual position during intercourse, ,29.2% indicated that the “sitting on top” position was better tolerated, whereas 21.8% preferred the supine position and 22.2% were more comfortable on the lateral decubitus (“spoon” position),.

Additionally, a partners’ desire may be tempered by their concern for causing pain and injury to the patient, a scenario that may lead to disappointment, friction inter-partner conflict. Trying different intercourse positions may be helpful, counseling with the patient and their partner may help them communicate better and reduce conflict. Since sexual dysfunction is a major contributor to the loss of self-esteem, depression, and social isolation may evolve.

List of common, non-specific symptoms associated with adhesive arachnoiditis:

- Constant low back pain that radiates to buttocks or legs, often sharp or burning

- Back pain worsening with prolonged sitting or standing

- Positional back pain, worsening or improving with sitting or standing

- Back or neck pain worsening with forward or backward flexion or tilting

- Leg weakness, may be asymmetric

- Loss of feeling or cold sensations in the legs

- Burning or prickling pain or tingling in the bottom of the feet

- Bizarre skin sensation (crawling insects, water dripping)

- Difficulty starting or stopping urination, incontinence with severe cases

- Blurred vision or ringing in the ears

- Headaches

Interpretation of Symptoms

The signs and symptoms that occur associated with AA often do not conform with the usual presentation of typical and common low badk pain and radiculopathy findings which may cast doubt about the patient’s truthfulness or credibility. This is due to the nature of the underlying pathology related to AA and the spotty and variable distribution of inflammation in affected tissues. For example, unlike the pain distribution pattern seen in a classic radiculopathy like sciatica — one that usually projects along a nerve trunk or follows a nerve dermatome — pain in patients with AA does not extend along a continuous path, but is present in regions or patches such as at the medial upper section of the thigh, or at the posterolateral aspect of the distal thigh or they may appear irregularly on the lateral distant portion of the leg. It may be accompanied by fasciculations in the early stages and by muscle spasms later on. It is important not to dismiss or deny credibiilty of symptoms presented in someone at risk for AA.

Different mechanisms are responsible for the different manifestations of pain and other findings in AA. for example, it is believed that autoimmune reactions play a role, as some patients appear to be more susceptible to develop more scarring and adhesions in the healing process than others. For a valuable exploration of the many mechanisms behind the varied symptoms and their relationship to the underlying conditions that contribute to the development of AA, please read Suspecting and Diagnosing Arachnoiditis – 2017.

Adhesive arachnoiditis, the most severe type of chronic arachnoiditis, results in scar tissue formation, which compresses nerve roots disrupting their blood supply and the normal flow of CSF. It can progress to arachnoiditis ossificans, an end-stage complication of adhesive arachnoiditis characterised by the pathological calcification of the spinal arachnoid in which calcium is deposited into the matrix of the affected membranes.

Risk Factors

Associated Medical Conditions:

As a consequence of impaired flow of CSF, the development of arachnoid cysts and syrinx (fluid collections in the spinal cord) have been reported.

Predisposing Medical Conditions:

- Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Marfan’s Syndrome

- Tarlov Cysts

- Kyphoscoliosis

- Rheumatoid Spondylitis

- Spinal Stenosis

- Osteoporosis

- Herniated Discs

- Spinal cord compression

- Spinal cord trauma

- Infection

- Toxic reactions to medications and chemicals

- Electrocution

Predisposing Procedures:

- Spinal surgery – especially multiple spinal surgeries

- Spinal injections (i.e. epidural injections, epidural blocks, myelograms), especially multiple

- Epidural spinal injections or myelogram dyes mistakenly injected into the intrathecal space

- One or multiple spinal taps.

- Difficult epidural blood patches (injection >20ml).

- Infections associated with meningitis (viral, fungal or bacterial).

In a 2017 publication reviewing 489 patients with adhesive arachnoiditis, the precise probable cause of AA was identified in 472 cases (96.5%); in the remaining 17 cases (3.5%), probable cause was deduced from the timing of sudden changes in the patient’s symptom intensity and frequency. The breakdown incidence of these 489 patients is shown below:

Myelogram with Pantopaque, (pre-1986) 12

Myelogram* followed by spinal surgery (post-1986) 16

One Laminectomy (first) 38

Laminectomy plus another procedure 18

Laminectomy, (2nd or multiple) 76

Spinal fusion with bone graft 36

Spinal fusion with hardware 71

Spinal anesthesia 45

Epidural anesthesia (Lumbar) 51

Epidural steroid injections (with incidental dural puncture) 53

Pseudomeningocele following dural tears at laminectomy 27

Other pain relief related procedure 29

Thoracic epidural anesthesia (syringomyelia) 5

Neuroplasty 5

Vertebroplasty 4

Spinal “taps” 3

Total: 489 patients

*In 1986, the production of oil-soluble contrast media for myelograms was discontinued in the USA.

Diagnosis of Adhesive Arachnoiditis

A diagnosis of AA is based upon assessment of a detailed patient history identifying key symptoms and risk factors such as having had an invasive procedure, surgery or serious illness within the spine. In addition, a physical exam and imaging tests such as a CT or an MRI for confirmation is essential. Since the symptoms of adhesive arachnoiditis resemble those associated with other spinal conditions, it is important to consider a multitude of alternative diagnoses.

Physical Examination

In patients with adhesive arachnoiditis, physical examination can reveal changes in reflexes, sensation and/or weakness. Exploration of proprioception (joint position awareness) can confirm symptoms of impaired balance.

Abnormal findings on physical exam, while non-specific, may commonly include:

- Pain on extension of arms

- Weakness of upper and/or lower extremities, often asymmetrical

- Inability or painful straight leg raise

- Restriction of range-of-motion in arms and/or legs

- Indentation of lower spine

- Pain when applying pressure over lower lumbar-sacral area

- Asymmetry of paraspinal area muscle groups

- Reduced reflexes in lower extremities, often asymmetrical

- Loss of touchand/orvibration sensation in foot, ankles, cold to the touch

Clinical Testing

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbosacral spine with contrast is the best imaging study because it is the most precise and lacks the radiation exposure associated with a computed tomography (CT) scan. The MRI uses a magnetic field and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of particular organs and bodily tissues instead of radiation.

However, the presence of certain non-titanium metal objects (screws, wires, etc.) makes the MRI contraindicated since it may heat these metals. If an MRI is contraindicated, the diagnosis of arachnoiditis can be made using a contrast CT scan, but this requires injecting contrast media into the intrathecal compartment of the spinal cord which is invasive and potentially could make the condition worse.

When routine MRI is inconclusive, an MRI performed after the administration of intrathecal gadopentate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA) as a contrast agent has been described as a safe, effective technique to diagnose or exclude the diagnosis of arachnoiditis. It should be noted that although a large multicenter study failed to demonstrate behavioral changes, neurologic alteration, or seizure activity following the use of intrathecal gadolinium, the administration of intrathecal gadolinium is not approved for use by the FDA and is used off-label. Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). These conditions have occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease and should therefore be avoided in patients with impaired kidney function.

While MRI is the gold standard in the diagnosis of arachnoiditis, unenhanced CT scan better identifies the presence and extent of calcification associated with arachnoid calcifications.

Findings on imaging studies suggestive of arachnoiditis include:

(1) intrathecal calcification

(12 enlarged or displaced nerve roots

(3) clumping of nerve roots

(4) adherence of nerve roots to the wall of the dural sac

(5) Intrathecal pseudocysts

(6) Abnormal pattern of dye distribution within the dural sac pseudomeningocele (see Figure 5) intradural scarring

(7) dural sac deformity or narrowing

(8) residual oil-soluble contrast media in the dural sac

(9) multiple deposits of contrast media with irregular distribution

(10) abnormal distribution of nerve roots within the dural sac

(11) extradural scarring in continuity with a deformed dural sac

Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies are not definitive in the diagnosis of adhesive arachnoiditis nor is clinical neurophysiological testing (e.g. electromyelography).

While definitive diagnosis of AA requires imaging, other tests contribute to understanding the risks of AA and may provide clues to the selection of treatment options. These tests include those that assess the presence of inflammation and altered hormonal balances that frequently accompany severe chronic pain. Addressing these conditions may prove helpful in reducing pain and improving function and quality of life.

Inflammatory Markers (blood tests):

-

- C-Reactive Protein-High Sensitivity (CRP-HS)

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

- Interleukins (IL-6)

- Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

Hormone Assessments (blood tests):

1. Pregnenolone

2.DHEA

3.Cortisol

4.Progesterone

5.Estradiol

6.Testosterone

Treatment of Adhesive Arachnoiditis (AA)

Because adhesive arachnoiditis is a rare disorder, there is no consensus on standard treatment of AA. There have been no well-designed studies to investigate specifice medical interventions. However, it clear that treatment is available that can provide significant improvement in symptoms and a return to a better quality of life. Forest Tennant MD, now retired, has had a great deal of experience in the management of AA and has proposed guidelines for practcioners.

Goals in Management of AA:

- Pain control

- Reduction of neuroinflammation

- Exercises to improve flow of spinal fluid

- Regeneration of damaged nerves

Pain Control

Because of the adhesive nature of the condition, sudden movements such as being bumped or jolted can be very painful. To help protect against this, spine bracing can be effective and AA patients may benefit from the periodic use of a lumbar or cervidal brace to protect them. However, excessive use of braces can contribute to muscle weakness. Care should be taken when walking in unfamiliar areas while shopping or attending social events.

The pain associated with AA is often severe and aggressive effort is required to provide relief. Medications directed at neuropathic (nerve) pain are indicated and should be initiated early with gradual increased dosing to achieve optimal benefit and avoid side effects. These medications include gabapentin (Neurontin), pregabalin (Lyrica) and supplements including palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), L acetyl-carnitine, lipoic acid and others possibly including CBD and medical cannabis.

See Neuropathic (Nerve) Pain

Because of the severity of AA, it is often necessary to turn to opioids to provide adequate pain control and improve function. While it always the case to limit the quantity and potency of opioids chosen for pain management as mucg as possible, it may be necessary to use higher potency opioids. However, the opioids which have greater effect on neuropathic pain may be preferred. These opioids include tramadol (Ultram), tapentadol (Nucynta), levorphanol and methadone.

However, any medication for pain may be only marginally effective unless spinal cord inflammation is first controlled.

Reduction of Neuroinflammation

Every AA patient must have a daily regimen to keep neuroinflammation from progressing. This can be the missing link to relief and recovery. This regimen includes gentle exercises to improve flow of spinal fluid and limit or reverse the adhesive process. The use of medications to reduce inflammation should also be included.

Recent advances in research into the inflammatory processes involving the nervous system (neuroinflammation) have provided insights into some of the unique mechanisms involved. Immune cells within the nervous system called the microglial cells are believed to play a role in the initiation and maintainence of neuroinflammation. Unfortunately, unlike other mechanisms of inflammation, microglial cells do not respond well, if at all, to standard anti-inflammatory drugs including ibuprofen and other NSAIDs or corticosteroid anti-inflammatories including hydrocortisone. Methylprednisolone 4 mg or prednisone 5 to 10 mg at 3:00 pm on 5 days a week may be recommended but corticosteroids must be used with caution under the guidance of a physician due to significant side effects associated with prolonged use.

See: Neuroinflammation

There is a strong effort being made by the medical community to identify medications that can reduce microglial activation of neuroinflammation but a definitively potent and effective medication is still elusive. However, there is a growing body of research that suggests some alternative medications may be safe and effective and should be considered, especially for those with severe symptoms. These medications include minocycline and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), both with evidence that they reduce microglia-induced neuroinflammation.

See: Minocycline (Coming soon)

See: Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA)

The role of an anti-inflammatory diet and anti-inflammatory supplements should not be overlooked. The Mediterranean, or anti-inflammatory, diet is an important component of chronic pain management, especially with conditions associated with chronic inflammation. Nutritional supplements, especially curcumin and other NRF2 activators are highly recommended for their antioxidant benefits related to inflammation.

See: Meriva (Curcumin)

See: Nutrition & Pain

Exercises to improve flow of spinal fluid

Mild physical therapy with emphasis on stretching is recommended for affected individuals to restore motion, preserve function and to help them remain active. Rocking in a rocking chair has been suggested as well as the judicious use of inversion tables in selected patients. Other approaches include massage, hydrotherapy, and hot or cold compresses. Surgery as a treatment of adhesive arachnoiditis is generally not recommended because of the possibility of worsening the inflammation and the condition.

It is particularly important that patient improve and maintain the range of motion of their spine and extremities as much as possible. This involves daily stretching so that eventually the patient can attain full range of motion, at least of their arms and legs. Patients should walk outside their home daily.

The following spinal cord exercises have been recommended by Dr. Forest Tennant, a leading authority in the management of adhesive arachnoiditis:

FULL-BODY STRETCH LAYING DOWN

Lay down on the floor and do a full-body stretch. Count up to 10.

FULL-BODY STRETCH STANDING

Spread hands and reach “to the sky” until you feel pressure and tugging in your back. Count up to 10.

SIT AND STRETCH ARMS

Stretch your arms and spread your fingers. Count up to 10. Can do while sitting in a car or plane.

LEG RAISE WHILE LAYING DOWN

Raise your leg until you feel tugging in your back. Count up to 10.

LEG RAISE WHILE STANDING

Stabilize yourself next to a table or wall. Raise your leg and flex your foot.

KNEE PULL WHILE LAYING DOWN

Pull your knee back until you feel tugging in your back. Count up to 10.

INVERSION TABLE

If able, a short episode on an inversion table may assist in pulling adhesions and cauda equina nerves apart to prevent scarring.

Regeneration of damaged nerves

Nutritional and hormone support may facilitate the body’s ability to repair damaged nerves. When hormonal deficiencies are identified, replacement therapy might be helpful in restoring nerve health.

- Supplement deficient hormones as determined by serum or saliva testing:

a) Pregnenolone

b) DHEA

c) Thyroid

d) Testosterone

e) Cortisol

f) Estradiol

g) Progesterone

- Vitamin B12: 2 to 3 times a week (sublingual or oral)

- OPTIONAL CONSIDERATION: Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG): 500 units, given sublingual or injection, 3 days a week. This treatment is off-label and lacks consensus of medical opinion as to it’s effectiveness.

- OPTIONAL CONSIDERATION: Add oxytocin (40 units per ml) given 1⁄2 ml sublingual twice daily if patient is making progress. This treatment is off-label and lacks consensus of medical opinion as to it’s effectiveness.

A Final Note

Many patients with AA cannot work, require assisted care and frequent doctor visits, and have undergone repeated procedures that only provided temporary pain relief and, even despite taking multiple medications including opiates, they continued to experience severe pain. Considering that the severity and chronicity of AA includes life-term suffering, psychological dysfunction, and physical disability — prevention of AA by far outweighs relying on any therapeutic effort.

This raises the question as to whether diagnostic (myelograms, spinal taps, discograms, etc.) or therapeutic invasions of the spine (laminectomies, fusions, epidural or spinal anesthesia, neuroplasties, epidural injections of steroids, etc.) should to be more limited. Since, at present, there is no definitive cure for this condition, emphasis needs to be placed on prevention. Invasive interventions in the spine should only be performed when absolutely necessary and only when such procedures have been shown to offer a definite benefit to the patient.

Finally, as noted above, there is little definitive research to guide the treatment of arachnoiditis. Much of the information on this web page has been gleaned from the work and pubications of Forest Tennant MD, a physician with special interest and extensive experience with the diagnosis and treatment of patients with arachnoiditis. I am grateful for his contribution to, and sharing of, his understanding of arachnoiditis and its management.

Resources

References

Adhesive Arachnoiditis – Overview

- Suspecting and Diagnosing Arachnoiditis – 2017

- Arachnoiditis – Clinical Progression, Evaluation, and Management- 2013

- Obstetric epidurals and chronic adhesive arachnoiditis – 2004

- Postlumbar puncture arachnoiditis mimicking epidural abscess – 2013

- Thoracic arachnoiditis, arachnoid cyst and syrinx formation secondary to myelography with Myodil, 30 years previously – 2006

- Adhesive arachnoiditis in mixed connective tissue disease – a rare neurological manifestation – 2016

- Arachnoiditis Following Caudal Epidural Injections for the Lumbo-Sacral Radicular Pain – 2013

- Adhesive arachnoiditis following lumbar epidural steroid injections – a report of two cases and review of the literature – 2019

- A rare cause of progressive neuropathy: Arachnoiditis ossificans :[PAUTHORS], Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology (IJPM)

- Adhesive arachnoiditis in mixed connective tissue disease – a rare neurological manifestation – 2016

- Fibromyalgia and arachnoiditis presented as an acute spinal disorder – 2014

- Increasing back and radicular pain 2 years following intrathecal pump implantation with review of arachnoiditis – 2013

- Increasing back and radicular pain 2 years following intrathecal pump implantation with review of arachnoiditis. – PubMed – NCBI – 2013

- Arachnoiditis ossificans associated with syringomyelia – An unusual cause of myelopathy – 2010

- Anestheisa Severe adhesive arachnoiditis resulting in progressive paraplegia following obstetric spinal anaesthesia -2012

- Arachnoiditis: Symptoms, types, causes, and treatment – 2018

- What is different about spinal pain? – 2012

Adhesive Arachnoiditis – Treatment

- Arachnoiditis handbook for Relief and Recovery – Forest Tenant 2016

- Arachnoiditis – Clinical Progression, Evaluation, and Management- 2013

Arachnoiditis Treatment – Minocyline

- Minocycline blocks lipopolysaccharide induced hyperalgesia by suppression of microglia but not astrocytes – 2015

- A novel role of minocycline: attenuating morphine antinociceptive tolerance by inhibition of p38 MAPK in the activated spinal microglia. – PubMed – NCBI

- Minocycline, a microglial inhibitor, blocks spinal CCL2-induced heat hyperalgesia and augmentation of glutamatergic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons – 2014

- Pathological pain and the neuroimmune interface – 2014

- Minocycline attenuates the development of diabetic neuropathic pain: possible anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms. 2011 – PubMed – NCBI

- Minocycline Provides Neuroprotection Against N-Methyl-d-aspartate Neurotoxicity by Inhibiting Microglia – 2001

- Minocycline targets multiple secondary injury mechanisms in traumatic spinal cord injury

.

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.