“The greatest evil is physical pain.”

– Saint Augustine

Prescription Medications:

Opiates/Opioids

Because the distinction between the terms “opiates” and “opioids” is often not appreciated, even by physicians, the terms are generally used interchangeably. However, they are a little different:

The term “opiate” refers to pain medications derived from opium, which comes from the opium poppy. Opiates include codeine, morphine, opium and heroin.

The term “opioid” refers to all opiate pain medications as well as synthetic pain medications that are structually similar to opiates. Synthetic opioids include hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone (Dilauded & Exalgo), oxymorphone (Opana), methadone, levorphanol, tapentadol (Nucynta) and others.

To gain a better perspective on current pain management with opioids, please read:

It is recommended to read the following sections to become familiarized with some of the terms and concepts related here:

See also:

- Neurobiology of Opioids

- Opioid Tolerance

- Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia

- Opioid Withdrawal

- Withdrawal-Induced Hyperalgesia

- Medications for Pain

- Alcohol, Pain & Opioids

- Opioid Blockers for Emergency Treatment of Opioid Overdose

- Opioid Dependence, Pregnancy & Breast Feeding

- Serotonin Syndrome

- TLR-4 Antagonists

Individual opioids:

- Buprenorphine (for Pain)

- Levorphanol

- Methadone (for Pain)

- Oxymorphone (Opana)

- Tapentadol (Nucynta)

Individual opioid antagonists (blockers):

Naloxone (for emergency reversal of opioid overdose)

Definitions and Terms Related to Pain

Key to Links:

- Grey text – handout

- Red text – another page on this website

- Blue text – Journal publication

[cws-widget type=text title=””]

.

“Nothing is intrinsically good or evil, but it’s manner of usage that make it so.”

– St. Thomas Aquinas

This Page:

- Opioid Dependence

- Opioid Tolerance

- Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

- Opioid Dosing – Long-Acting vs Short Acting Opioids

- Opioid Dosing – Time-Scheduled vs As-Needed Opioid Dosing

- Opioids – Potency and Morphine Equivalency

- Opioids – Morphine Equivalency and Risk for Overdose

- Opioids Compared With One Another

- Opioid Mu-Receptor Affinity

- Opioids Synergy with Other Medications

Opiates/Opioids

Opioids have been in use for the treatment of pain for millennia and remain the best, most effective means for treating chronic pain for millions of people. While there is no argument that the inappropriate use of opioids can lead to addiction and fatal outcomes, by far the majority use of opioids in the management of pain is safe and effective, allowing for the return of quality of life to those suffering from chronic pain. The information that follows is directed at educating both our patients and their families about opioids so that their prescription use can be safe and effective.

For an overview of pain management with opioids, please read our informed consent for treatment:

Opioids for Chronic Pain Management

To begin to understand and communicate about opioids, one must first learn some terminology to regarding the characteristics of opioids.

Opioid Dependence

“Dependence,” sometimes qualified as “physical dependence,” on opioids is a normal physiologic adaptation defined as the “development of withdrawal or abstinence syndrome with abrupt dose reduction or administration of an antagonist.”

Unfortunately, the term “dependence” in the past was a term that was synonymous with addiction, based on the erroneous belief that physical dependence equated to addiction. It does not. The nervous system is highly homeostatic, in other words it modifies it’s function when exposed to medications that alters it’s functions in order to maintain balance. Medications associated with dependence are not limited to opioids, but in fact, include many medications that affect the nervous system most especially many antidepressants, anxiety medications, sleeping medications and even some blood pressure medications.

Examples of Dependence

For example, when opioids interact with opioid receptors in the neural network of the gut resulting in the slowing of intestional contraction that sometimes leads to constipation, the neural network of the gut adapts to the slowing efffect of the opioid by enhancing neural activity to balance the slowing and return bowel function to normal or near normal in most cases. If the opioid is suddenly stopped, or withdrawn, the increased gut neural activity is now no longer balanced by the slowing induced by the opioid and the result is diarrhea and abdominal cramps – the hallmark symptoms of Opioid Withdrawal. Another common example is illustrated by the severe insomnia experienced by people who suddenly discontinue their use of benzodiazepines such as Xanax, Valium or Klonopin.

Severity of Dependence

Opioid dependence develops gradually over weeks to months as a person is continuously exposed to opioids. The severity of opioid dependence, as measured by the severity of associated withdrawal symptoms, is variable between people and dependent in large part on the amount and length of time that a patient has taken opioids. Intermittent use of opioids, characterized by periods of opioid-free time, will not result in the development of dependence. The mechanism by which opioids create dependence remains poorly understood. However, recent research implicates NMDA receptor activity in the process and the use of NMDA inhibitors may slow or reverse the development of opioid tolerance (see NMDA receptors below). Further research is required.

Treating Dependence (Avoiding Withdrawal)

For most people taking opioids chronically, dependence is unavoidable. However, was is avoidable is experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms. Abruptly discontinuing chronic use of opioids will generally trigger significant withdrawal symptoms when high opioid dosing has been experienced for an extended period of time. To avoid significant withdrawal symptoms it is only necessary to slowly taper down and off the opioid. The rate of taper is uniquely dependent on the individual and their opioid dosing history. But if the taper is slow, the dependence can be reversed completely and with minimal to no withdrawal symptoms. As a rule of thumb, to avoid withdrawal symptoms with opioids, reduce the opioid dose by no more than 10% at a time and proceed slowly by making a 10% reduction of the current dose every 1-4 weeks, as tolerated. Tailoring the rate of reduction based on the individual’s needs will simplify the process and make it very tolerable.

Opioid Tolerance

Tolerance refers to a normal neurobiological process characterized by the need to increase the dose of a medication over time to maintain the original effect. Tolerance is the result of the nervous system adapting to the effects of a medication, a process referred to as neural plasticity. Some people build tolerance more quickly than others. The process of tolerance occurs at different rates for different effects and different medications within the same class. For example, tolerance to the nausea and sedative effects of opioids builds fairly quickly, usually measured in days, sometimes weeks. In most people, the build-up of tolerance to the analgesic (pain-relieving) benefit of opioids occurs much more slowly, usually measured in years. In some cases, such as constipation with opioids, tolerance does seem to develop at all so that despite taking the same opioid for weeks or months, the constipation associated with that particular opioid may never improve, necessitating a change to another opioid.

Understanding opioid tolerance is critical to their safe use – please see Opioid Tolerance for more information.

Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH), defined as an increased response to a painful stimulus caused by exposure to opioids, is the subject of current debate regarding it’s clinical significance. Research suggests that the use of opioids possibly results in a change in the nervous system that results in painful stimuli being perceived as even more painful because of previous exposure to opioids. The clinical extent of this condition remains uncertain and it’s clinical significance is highly unlikely. In the current climate of political turmoil regarding the prescribing of opioids, OIH is often presented as an argument against the use of opioids for chronic pain. At this point in history, the research to support clinically significant OIH in the usual prescribing patterns of opioids for chronic pain is indeed very weak. That being said, there may be steps one can take to reduce OIH as a measure of prevention.

For more information about OIH: Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH)

Opioid Dosing – Long-Acting vs Short Acting Opioids

There is conflict of opinion and inadequate evidence for definitive guidelines for managing pain with long-acting (LA-opioids) vs. short acting opioids (SA-opioids).

The argument in favor of the use of SA-opioids is that they provide greater flexibility in dosing based on need associated with variable levels of pain reflecting changing activities of daily living. For many patients, pain is not consistent throughout a 24 or even 12 hour period, nor from day to day, and therefore analgesic use is preferred to be based on need which can be better met with SA-opioids. Furthermore, some activities are preferred to be avoided while taking an opioid such as driving and the SA-opioids provide greater adaptability to patient’s perceived need. SA-opioids are also generally more affordable.

The argument against SA-opioids is that the burst effect of a rapidly rising opioid blood level reinforces the psychological desire to take the opioid which could possibly lead to greater opioid abuse or addiction. However, research does not show increased risk of abuse or addiction associated with the use of SA opioids.

The argument in favor of the use of LA-opioids is that they provide extended, continuous benefit so that a patient is not frequenly interrupted throughout the day by uncontrolled pain demanding a break in attention and activity to administer the medication. This freedom from pain interruption is paralleled by the prolonged psychological freedom of being reminded of the pain condition and the accompanying emotional response. When employed for nightime use, the LA-opioids provide greater freedom from pain-interrupted sleep and less morning pain upon awakening.

The argument against LA-opioids is loss of flexibility in adaptive dosing and their potential for greater overdose risk when taken on an as-needed basis in response to perceived increased need. Furthermore, the use of LA-opioids at night may potentially be of greater risk in the event of untreated sleep apnea due to their higher blood levels toward the end of the usual sleep cycle when there may be greater sensitivity to respiratory depression. LA-opioids are also generally less affordable. Research also suggests that LA-opioids may develop tolerance faster than SA-opioids.

Please read: “Long-Acting Opioids Safety information“

While research is still lacking to establish definitive recommendations regarding the use of short-acting opioids vs. long-acting opioids vs. a combination of the two, studies have established that there is a greater potential for unintentional opioid overdose in patients taking both short-acting and long-acting opioids. When prescribed short-acting opioids for break-through pain while taking long-acting opioids, the use of short-acting opioids should be limited to an “as needed, only as prescribed” basis, and not used “by the clock” or as a preventative measure. When the use of long-acting opioids is required, the number of short-acting opioids used should be kept to a minimum as needed.

Opioid Dosing – Time-Scheduled vs As-Needed Opioid Dosing

There is also conflict of opinion and inadequate evidence for definitive guidelines in managing pain with time-scheduled dosing (opioids dosed by the clock) versus dosing based on perceived need for pain control. The argument in favor of as-needed dosing is that it provides a greater sense of control and in some cases allows for reduced use when there is reduced need. For many patients, pain is not consistent throughout a 24 or even 12 hour period, nor from day to day and therefore analgesic use is preferred to be based on need. Furthermore, some activities are preferred to be avoided while taking an opioid such as driving and the SA-opioids provide greater adaptability to patient’s perceived need.

There is also a lack of consensus on the comparative effectiveness of the use of long-acting (LA) opioids only vs. short-acting (SA) opioids only vs. a combination of long-acting and short-acting opioids.

A study published in 2011 reported that “time-scheduled dosing typically results in higher dosage levels and is associated with higher levels of patient concerns about opioid use.”

The CDC recently concluded that due to a statistical increased risk of overdose when LA a

nd SA opi

oids are prescribed together, it is recommended that combining the two together should be avoided. However, a recent study that focused on this question and adjusted the risk in context with total morphine equivalency dosing concluded there is no evidence of greater overdose risk associated with LA and SA opioids prescribed together. Ultimately, the answer to improving opioid prescribing safety rests on providing the patient with proper education regarding safe guidellines for use.

Opioids – Potency and Morphine Equivalency

Since all opioids have different potencies, when comparing doses of different opioids, especially when converting from treatment with one opioid to another, a comparism of equivalent dosing must be esstablished. This is done using morphine as the standard of comparism. Dosing of opioids is standardized by comparing a milligram dose of an opioid with the equivalend milligram dose of morphine.

For example:

If an opioid is equally as potent as morphine (i.e. hydrocodone/Norco), than it’s morphine milligram equivalents (MME) conversion value is 1.0 and a dose of four 10mg tablets/day of that hydrocodone would be 40mg/day multiplied by 1.0 and equal to 40 MME/day.

Another example:

if an opioid is 3x as potent as morphine (i.e. oxymorphone/Opana), than it’s morphine milligram equivalents (MME) conversion value is 3.0 and a dose of four 10mg tablets/day of that oxymorphone would be 40mg/day multiplied by 3.0 and equal to 120 MME/day.

Commonly used conversion values for morphine equivalent doses are as follows:

- Codeine – 0.15

- Tapentadol – 0.4

- Hydrocodone – 1.0

- Morphine – 1.0

- Oxycodone – 1.5

- Oxymorphone – 3.0

- Hydromorphone – 4.0

- Levorphanol – 8.0

- Fentanyl (in mcg/hr) – 2.4

- Buprenorphine – 40.0

- Methadone –

- 1-20 mg/day – 4.0

- 21-40 mg/day – 8.0

- 41-60 mg/day – 10.0

- 61+ mg/day – 12.0

As noted above, methadone’s potency is enhanced at higher doses, one of the contributing factors to the complexity of prescribing methadone and a strong argument for limiting incremental doses of methadone when raising the dose.

Asymmetric Morphine Equivalency

In addition to the incomplete accuracy of the morphine equivalent values, it is also necessary to understand that the equivalency may vary when moving from opioid 1 to opioid 2 as compared to moving from opioid 2 to opioid 1. This is at least partly due to the concept of incomplete tolerance and the asymmetry of tolerance when moving from one opioid to another (See Opioid Tolerance). For example, in a study evaluating morphine and hydromorphone, when rotating from morphine to hydromorphone (Dilaudid), the equivalency ratio of morphine to hydromorphone (morphine:hydromorphone) was determined to be 5.33:1, whereas when rotating from hydromorphone to morphine, the ratio was 3.8 to one. This underscores the uncertainty of calculating an “equivalency” between opioid analgesic dosing and the need for caution when switching from one opioid to another.

Two Important Caveats

- When rotating from one opioid to another, a patients tolerance to the current opioid is likely to be higher than their tolerance to the new opioid. As a result of this incomplete cross tolerance, it is safer to reduce the dose of the new opioid below the morphine equivalent dose to avoid side effects associated with possible excessive dosing/overdose.It is generally recommended that the dose reduction of the new opioid be from 25-50% or even more reduction in the case of methadone.

- It should be understood that these conversion values are only estimates and there is actually very little research that actually verifies their accuracy. Furthermore, the relative potency of one opioid to another may vary considerably from one person to another due to that person’s genetic variations and the presence of other medications or supplements that can significantly impact how the opioid is metabolized and eliminated from the person’s system.

Please read: The myth of morphine equivalency

Opioids – Morphine Equivalency and Risk for Overdose

To state the obvious, higher doses of opioids are associated with increased risk of abuse and of serious overdose. In comparing relative risk of low dose opioids to higher doses, research suggests the dose-dependent association with risk for overdose death (relative to 1–19 MME/day), the adjusted odds ratio (OR) is:

- 1.32 for 20–49 MME/day

- 1.92 for 50–99 MME/day

- 2.04 for 100–199 MME/day

- 2.88 for ≥200 MME/day

In other words, when MME dosing is between 20 and 49mg/day, the risk of abuse/overdose is about 30% higher, it is about twice as high when MME dosing is between 50 and 200mg/day and nearly 3x as high when MME is more than 200mg/day. While not noted by the CDC Guidelines, recent research on prescription opioid overdose deaths in North Carolina in 2014 indicates that while the risk ratios of overdose risk climb somewhat steeply between 10 and 200, the rate of increased risk lessens as as MME exceeds 200.

What does not appear to have been evaluated in arriving at these statistics is a stratification of the overdose risk in context with how long a duration of treatment at a particular MME level. Presumably the risk of overdose would be higher in transition periods to higher MME than in patients at a same MME for an extended period of time.

Also, it should be emphasized that there are many variables that contribute to how a patient arrived at being prescribed higher MME of opioids. These variables are very likely to be significant contributors to the increased risks associated with high MME doses. While the MME number itself does suggest independent risk, it is extremely important to evaluate the many other contributing variables that are likely to be much more important than the MME number itself. This is especially true when applying risk assessment on an individual patient basis.

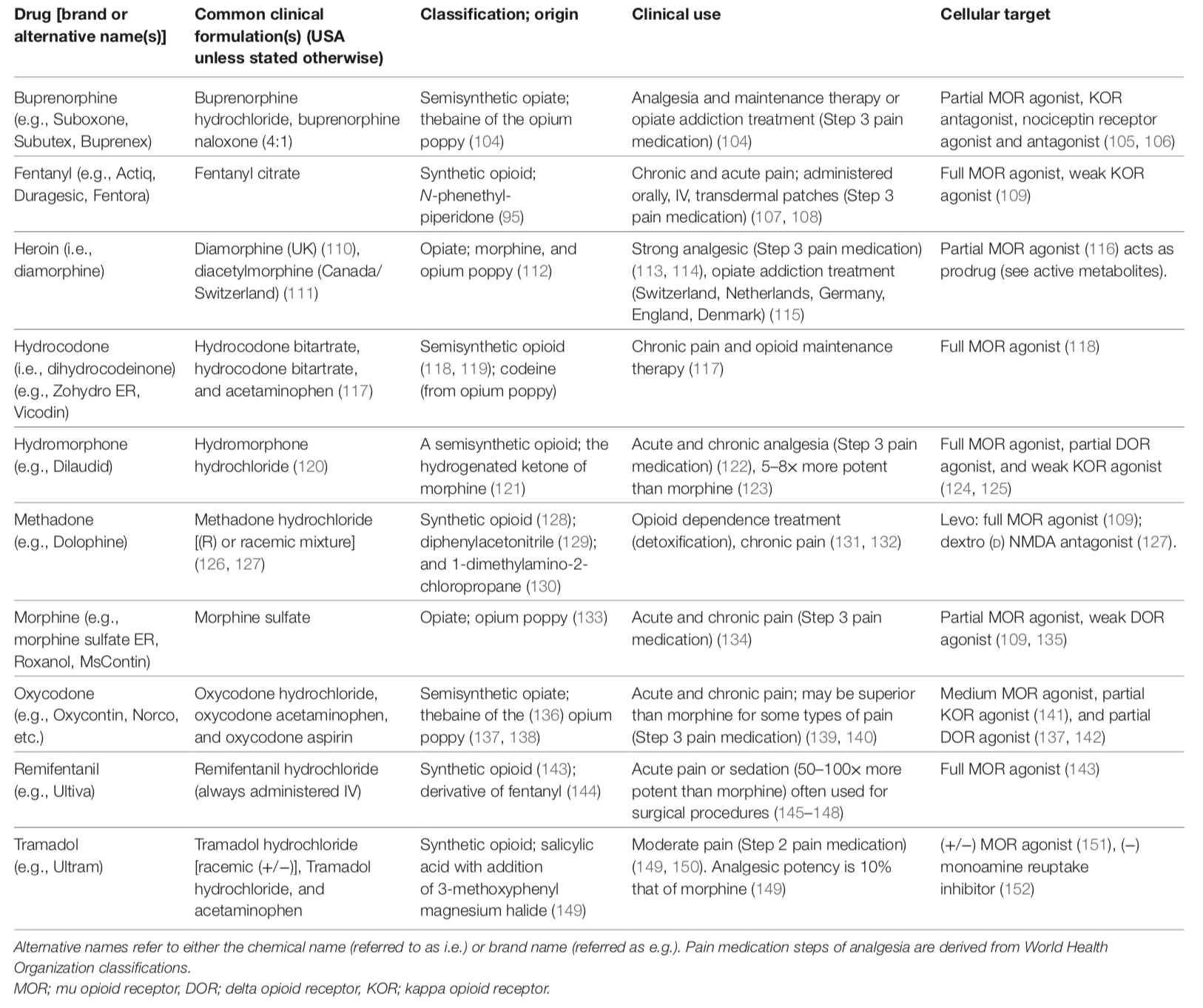

Opioids Compared With One Another

Descriptive and clinically relevant information of common opioids including clinical formulations, class of opioid, clinical uses, and cellular targets:

from: Pain Therapy Guided by Purpose and Perspective in Light of the Opioid Epidemic – 2018

(see link below)

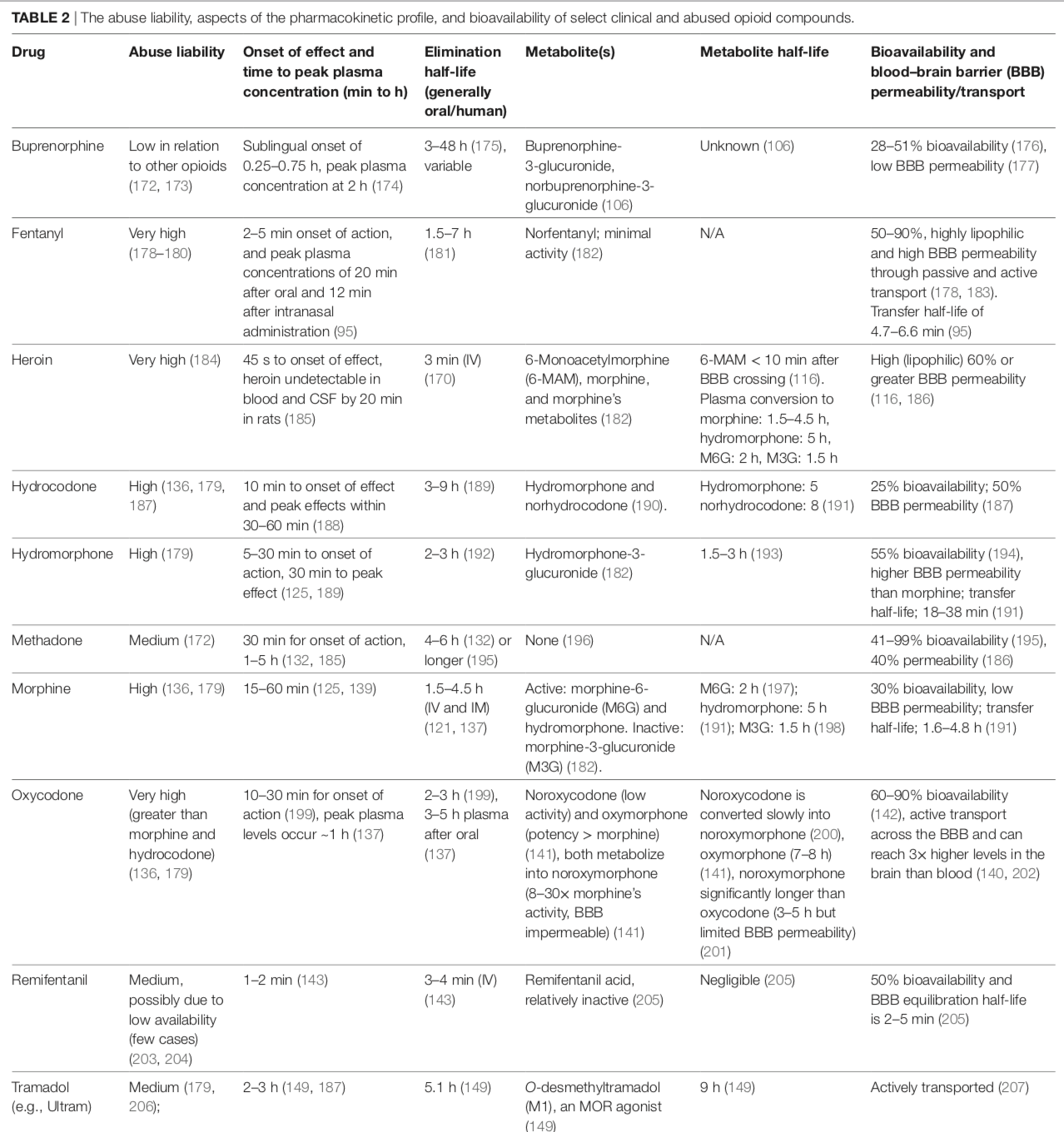

The abuse liability, aspects of the pharmacokinetic profile, and bioavailability of select clinical and abused opioid compounds:

from: Pain Therapy Guided by Purpose and Perspective in Light of the Opioid Epidemic – 2018

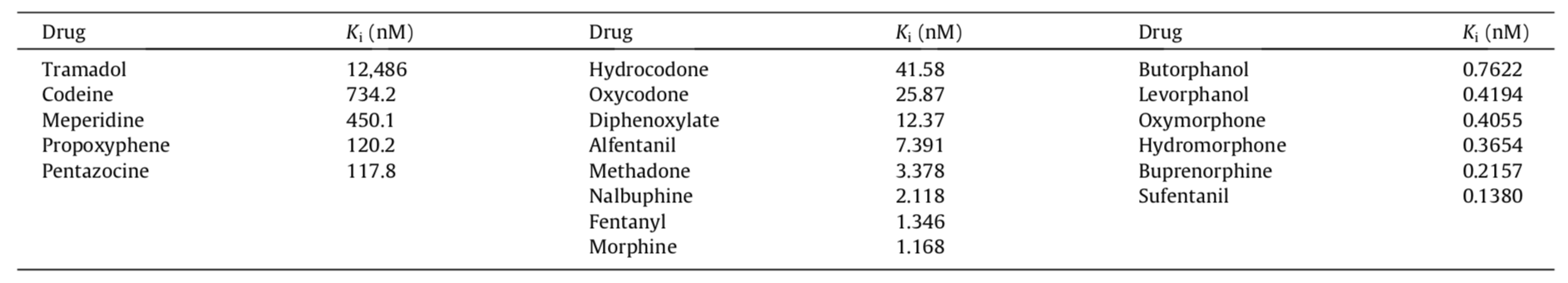

Opioid Mu-Receptor Affinity

The strength or degree of binding of a drug to its receptor is referred to as its affinity. It is analogous to the strength of a magnet, the stronger the magnet, the greater affinity it has for iron, An opioid’s affinity to the mu-opiod receptor can be important when a combination of opioids is present, especially buprenorphine and naltrexone (an opioid antagonist). If the affinity of the second opioid is less than the first, i.e. buprenorphine or naltrexone, it will be displaced from the receptor when both are present. So when naltrexone is given for an opioid overdose, it will be effective as long as naltrexone has greater affinity than the overdose opioid. When their affinities are closely matched, it requires higher doses of naltrexone to be effective, if at all, especially when the overdose opioid’s affinity is greater than naltrexone.

This principle also applies to the use of buprenorphine. At the high doses of buprenorphine used for addiction management to block the effect of another opioid used for abuse, the buprenorphine will be effective as long as its affinity is stronger then the opioid used for abuse. At the lower doses of buprenorphine used in treating pain, however, the affinity concerns becomes less important due to higher levels of un-occupied receptors that allow for both opioids to exert their effects simultaneously.

Affinity is quantified using Ki values, and the smaller the Ki value, the stronger the binding affinity to the receptor:

</t r>

| Opioid | Range of Ki Value |

| Levorphanol | 0.19 to .2332 |

| Buprenorphine | 0.21 to 1.5 |

| Naltrexone | 0.4 to 0.6 (antagonist effects) |

| Hydromorphone |

0.6 |

| Fentanyl | 0.7 to 1.9 |

| Methadone | < b>0.72 to 5.6 |

| Oxymorphine | 0.97 |

| Naloxone | 1 to 3 (antagonist effects) |

| Morphine | 1.02 to 4 |

| Pentazocine | 3.9 to 6.9 |

| Hydrocodone | 19.8 |

| Oxycodone | 23 |

| Codeine | 65 to 135 |

| Tramadol | > 100 |

However, different authorities do not always agree as to affinities. The following is another published listing of opioid mu-receptor affinities:

Opioids Synergy with Other Medications

“Synergy” occurs when the combination of two or more medications results in a greater response than the simple additive response of the individual medications. These supra-additive interactions are potentially beneficial clinically; by increasing effectiveness and/or reducing the total drug required to produce sufficient pain relief, undesired side effects can be minimized.

Opioids and Other Opioids

While in most cases the addition of a second opioid to the management of pain with an opioid, the second opioid simply provides an additive effect that would be predicted by the presumed sum of their predicted individual effects. However, their may be combinations that would allow for synergistic, supra-additive benefit for analgesia.

Morphine and Pentazocine (Talwin)

A small study of 20 patients that evaluated the combined use of morphine and pentazocine discovered the combination of morphine and pentazocine produce a level of analgesia significantly greater than can be accounted for by simple addition of the analgesic effects of each opiate analgesic alone. It was proposed to be due to interaction between the two mechanisms of action of the mu- and kappa-opioid receptors.

Opioids and Clonidine

Clonidine (Catapres) is a medication commonly used in the treatment of high blood pressure and is classified as an α2-adrenoceptor agonist. Opioid and α2-adrenoceptor agonists are potent analgesic drugs and their analgesic effects can synergize when co-administered. In spite of a large body of preclinical evidence describing their synergistic interaction, combination therapies of opioids and α2-adrenoceptor agonists remain underutilized clinically. Clonidine has been found to offer potential significant benefit in treating certain chronic pain conditions including diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia and chronic headaches as well as being effective in the management of opioid withdrawal. A synergistic analgesic benefit for neuropathic pain has also been proposed for clonidine with dextromethorphan.

Opioids and Other Potential Synergistic Options

Numerous other synergistic benefits with opioids have been proposed, including morphine with gabapentin or ketamine, tapentadol with pregabalin and tramadol with venlafaxine or doxepin.

See: Gabapentin (Neurontin) & Pregabalin (Lyrica)

References:

Opioid Pain Management Program

Opioids: Policies, Agreements & Informed Consents

- Opioids for Chronic Pain Management – Informed Consent 9-29-2015

- Medications, Opioids and Pregnancy Agreement

- Patient Counseling Document on Extended-Release Analgesics 12-13-2014

- Buprenorphine – fo

r Pain, Informed C

onsent

Opioids – Individual

Opioids – Buprenorphine (Butrans, Belbuca, Suboxone, Subutex, Zubsolv, Bunavail)

Opioids – Fentanyl (Duragesic)

Opioids – Hydrocodone (Norco, Vicodin)

Opioids – Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo)

Opioids – Levorphanol

Opioids – Methadone (Dolobid)

Opioids – Oxycodone (Percocet, Oxycontin, Xtampza ER)

Opioids – Oxymorphone (Opana, Oxycmorphone ER, Opana ER)

Opioids – Morphine (MSIR, MSER, MSContin)

Opioids – Tapentadol (Nucynta)

Opioids – Tramadol (Ultram, Ultracet)

Opioids – Long-Acting

Opioids – Overviews

- Pain Therapy Guided by Purpose and Perspective in Light of the Opioid Epidemic – 2018

- Opioid Agonists, Partial Agonists, Antagonists- Oh My! (Fudin) – 2018

Opioids – Neuropathic (Nerve) Pain

- Opioids and Chronic Neuropathic Pain – 2003

- Novel Treatments for Neuropathic Pain Syndromes – 2009

- Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain – Revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society – 2014

- Efficacy and safety of opioid agonists in the treatment of neuropathic pain of nonmalignant origin – Sec 6 – 2005

- Opioids and Neuropathic Pain – 2012

- Treatment_of_Neuropathic_Pain_The_Role_of_Unique_Opioid_Agents_-_2016

- Clinical practice guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain – a systematic review -2016

Opioids – Potency & Morphine Equivalency (ME)

- Web-based Opioid Dose Calculator

- Switching from Methadone to a Different Opioid

- Variability-in-opioid-equivalence-calculations

- The-myth-of-morphine-equivalency

Opioids – Rotation from One Opioid to Another Opioid

- opioid-rotation-in-patients-with-cancer-pain-a-retrospective-comparison-of-dose-ratios-between-methadone-hydromorphone-and-morphine-1996

- toward-a-systematic-approach-to-opioid-rotation-2014

- opioid-rotation-in-clinical-practice-2012-pubmed-ncbi

- feasibility-study-of-rapid-opioid-rotation-and-titration-2011

- feasib

ility-study-of-rapid-opioid-rotation-and-titration-is-it-truly-feasible-or-paradoxical-2011 - opioid_rotation___methods_and_cautions-2012

- a-multicenter-primary-care-based-open-label-study-to-assess-the-success-of-converting-opioid-experienced-patients-with-chronic-moderate-to-severe-pain-to-morphine-sulfate-and-naltrexone-2015

- the-opioid-rotation-ratio-of-hydrocodone-to-strong-opioids-in-cancer-patients-2014

- opioid-rotation-from-oral-morphine-to-oral-oxycodone-in-cancer-patients-with-intolerable-adverse-effects-2008

- the-opioid-rotation-ratio-from-transdermal-fentanyl-to-strong-opioids-in-patients-with-cancer-pain-pubmed-ncbi

- opioid-rotation-in-patients-initiated-on-oxycodone-or-morphine-2013

Opioids – Synergy with other Medications

- Analgesic synergy between opioid and α2-adrenoceptors – 2014

- Clonidine May Help in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) and Fibromyalgia Because – 2013

- Idiopathic Peripheral Neuropathy Responsive to Sympathetic Nerve Blockade and Oral Clonidine – 2012

- Clonidine – clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use in pain management

- Clonidine for management of chronic pain – A brief review of the current evidences – 2014

- Determination of adrenergic and imidazoline receptor involvement in augmentation of morphine and oxycodone analgesia by clonidine and BMS182874. – PubMed – NCBI

- Tramadol antinociception is potentiated by clonidine through α₂-adrenergic and I₂-imidazoline but not by endothelin ET(A) receptors in mice. – PubMed – NCBI

- THE ROLE OF TOPICAL AGENTS IN PODIATRIC MEDICINE – 2013

- Topical clonidine for neuropathic pain – 2015

- Pharmacologic Treatments for Neuropathic Pain

- Gabapentin enhances the analgesic effect of morphine in healthy volunteers. – PubMed – NCBI

- synergism-between-the-analgesic-actions-of-morphine-and-pentazocine-pubmed-ncbi

Opioids – Time-Scheduled vs As-Needed Opioid Dosing

- Association Between Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Opioid Overdose-Related Deaths

- Time‐scheduled vs. pain‐contingent opioid dosing in chronic opioid therapy – 2011

Prescription Opioids – Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – 2016

- CDC – Contextual evidence review for the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – 2016

- ASIPP Guidelines for Responsible Opioid Prescribing – Part I – Evidence Assessment 2012

- ASIPP Guidelines for Responsible Opioid Prescribing – Part 2 Guidance 2012

Opioids – Topically Applied

Opioids: Side

Effects and Complications

Opioi

ds: Side Effects – Overviews

Opioids Overdose: Emergency Reversal Agents

- Naloxone – Home Safety for Emergency Opioid Overdose – handout

- CVS and Walgreens to sell opioid overdose antidote without individual prescription in Louisiana 5-26-16

Opioids Overdose: Mechanisms

Opioids Overdose: Respiratory Depression

Opioids Complications: Tolerance

- Opioid Tolerance – the Clinical Perspective

- Differential development of antinociceptive tolerance to morphine and fentanyl is not linked to efficacy in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of the rat – 2012

- Opioid-induced Central Immune Signaling – Implications for Opioid Analgesia – 2015

Opioids Complications: Withdrawal

Opioid Complications: Hormonal Changes

Opioid Complications – Effects on the Immune System

- A Review of the Effects of Pain and Analgesia on Immune System Function and Inflammation: Relevance for Preclinical Studies – 2019

- The Role of Opioid Receptors in Immune System Function – 2019

- How I treat pain in hematologic malignancies safely with opioid therapy – 2020

- Do All Opioid Drugs Share the Same Immunomodulatory Properties? A Review From Animal and Human Studies – 2019

- Effects of systemic and neuraxial morphine on the immune system – 2019

- Long-acting Opioid Use and the Risk of Serious Infections: A Retrospective Cohort Study – 2018

- Immune function after major surgical interventions: the effect of postoperative pain treatment – 2018

Opioids – Safe Disposal

- Safe Disposal of Medicines > Disposal of Unused Medicines: What You Should Know

- Safe Disposal of Medicines > Medication Disposal: Questions and Answers

- Flush list Guide for Medicines

Emphasis on Education

Accurate Clinic promotes patient education as the foundation of it’s medical care. In Dr. Ehlenberger’s integrative approach to patient care, including conventional and complementary and alternative medical (CAM) treatments, he may encourage or provide advice about the use of supplements. However, the specifics of choice of supplement, dosing and duration of treatment should be individualized through discussion with Dr. Ehlenberger. The following information and reference articles are presented to provide the reader with some of the latest research to facilitate evidence-based, informed decisions regarding the use of conventional as well as CAM treatments.

For medical-legal reasons, access to these links is limited to patients enrolled in an Accurate Clinic medical program.

Should you wish more information regarding any of the subjects listed – or not listed – here, please contact Dr. Ehlenberger. He has literally thousands of published articles to share on hundreds of topics associated with pain management, weight loss, nutrition, addiction recovery and emergency medicine. It would take years for you to read them, as it did him.

For more information, please contact Accurate Clinic.

Supplements recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger may be purchased commercially online or at Accurate Clinic.

Please read about our statement regarding the sale of products recommended by Dr. Ehlenberger.

Accurate Supplement Prices

.